|

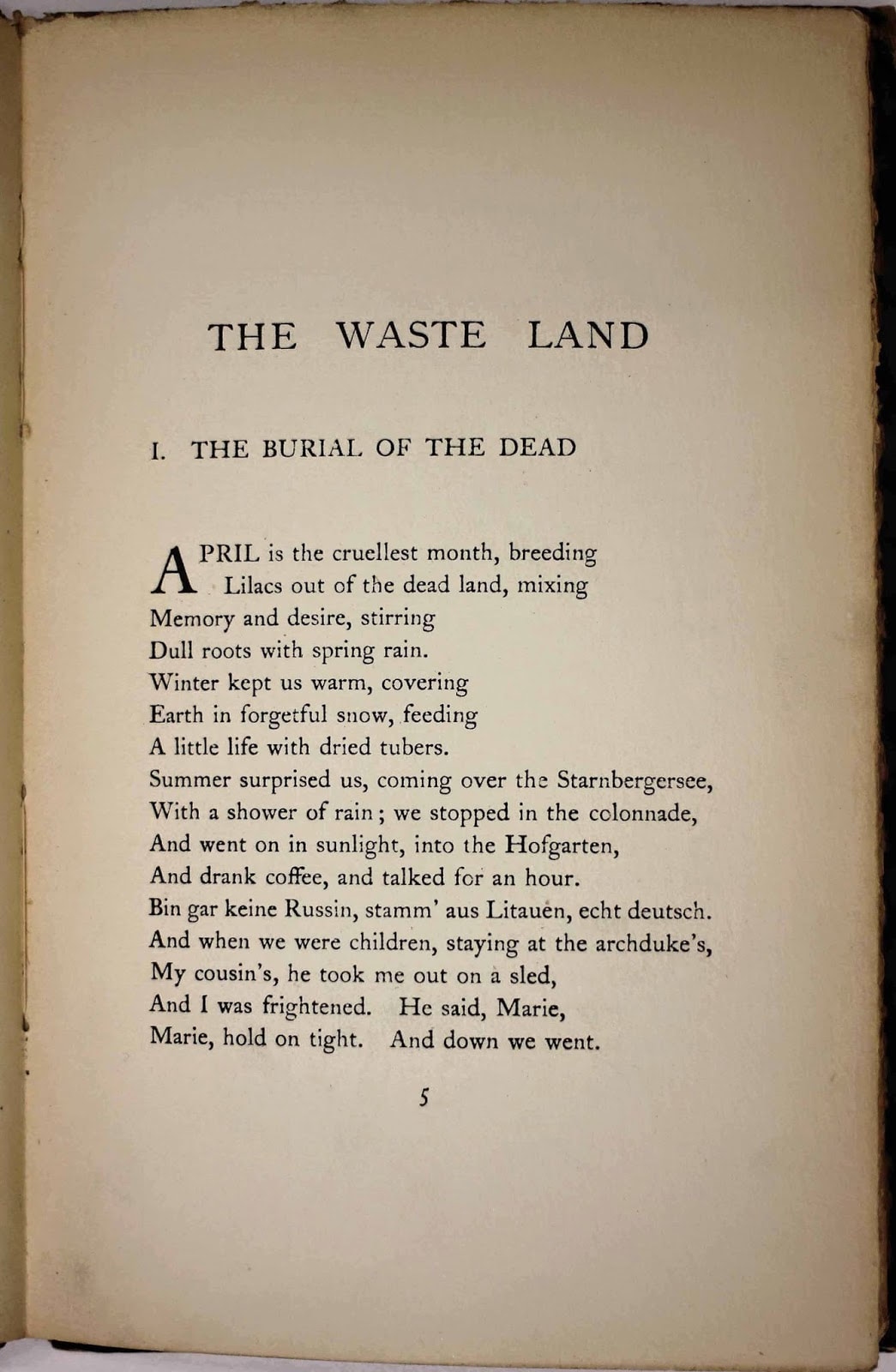

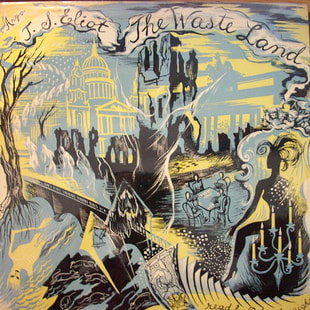

No one who has had the misfortune of reading anything I've written would ever accuse me of being 'literary' in style or technique. I write like a weekend carpenter - measure twice, cut once, use screws instead of nails so that pulling it down to do it properly the second time will be easier. However, to my surprise, I was invited by author and academic, Clare Rhoden, to submit a short literary work to an anthology inspired by T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Re-reading it, I was inspired to scribble the first short story I've written in years, fueled by coffee and a mix of bleak political anger and the existential dread that creeps like black mold up the walls of our era. To my additional surprise, she accepted my piece. I can only shudder to think of poor Eliot turning in his grave. Soon to be published by the UK imprint, PS Publishing, my modest effort* will sit beside those of real writers in an anthology called From the Waste Land. They are a mix of ghost stories, sci-fi, fantasy and apocalyptic tales, all inspired by Eliot's masterpiece of modernism, born in the wake of The Great War, an awful global war that could never, ever happen again....until it did. Death by Water, by Grace Chan A Winter Respite, by Clare Rhoden She Who Walks Behind You, by Leanbh Pearson The Watcher of Greenwich, by Laura E. Goodin Exhausted Wells, by Tee Linden Rats Alley, by Jeff Clulow Fragments of Ruin, by B.P. Marshall Dead Men, by Cat Sparks A Dusty Handful, by Aveline Perez de Vera Lidless Eyes That See, by Geneve Flynn A Witch’s Bargain, by Rebecca Dale And Fiddled Whisper Music on Those Strings, by Eugen Bacon Mountain of Death, by Austin P. Sheehan Fawdaze, by Rebecca Fraser Over the Mountains, by Tim Law A Shadow in This Red Rock, by Louise Zedda Sampson Dry Bones, by Robert Hood April, by Francesca Bussey The Violet Hour, by Nikky Lee We argued about the image for the cover. This was my suggestion... ...but, sadly, I understand they're going with something artistic instead. Probably in keeping with one of the original covers of Eliot's work. Which is, to be fair, probably for the best. *When I say 'modest' I'm being shamefully immodest, as I suspect my contribution will stand out amongst the others as this vehicle would stand out on the set of Mad Max. That said, I am honestly looking forward to reading the others' work, and see what resonated with them, and how it was expressed. If you're wondering about mine, I think this movie poster is close to my concept, two men, standing very close, wondering wtf. Enjoy!

0 Comments

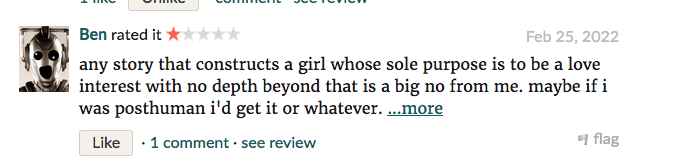

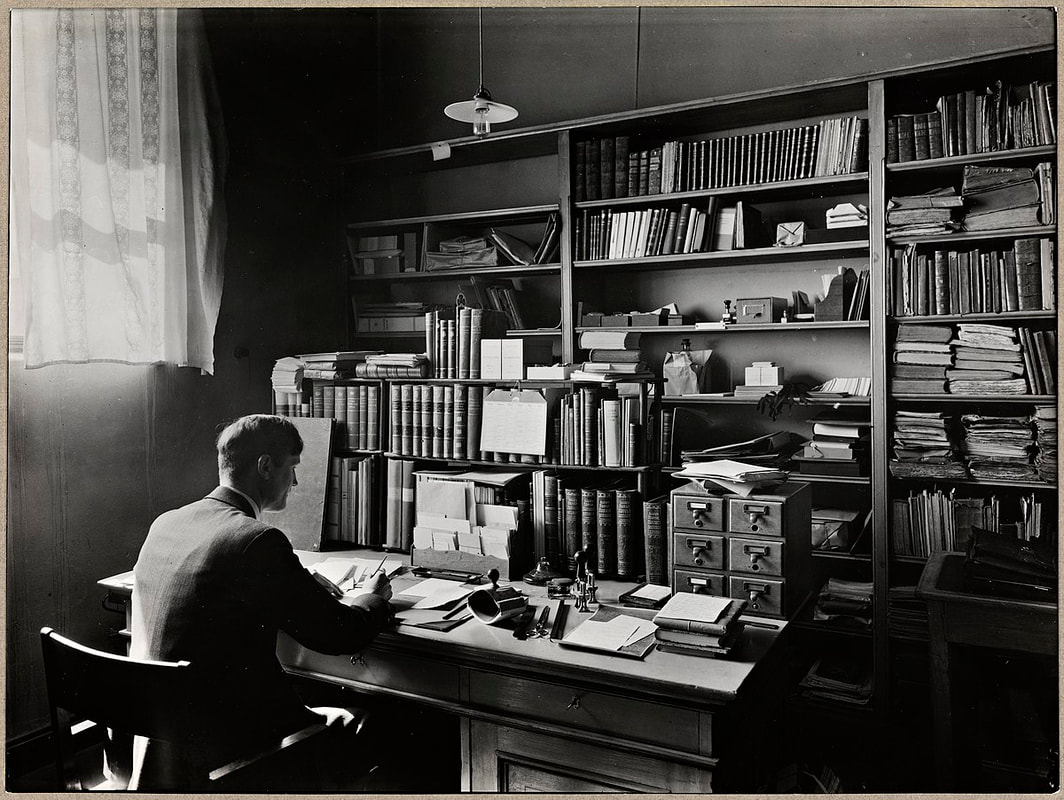

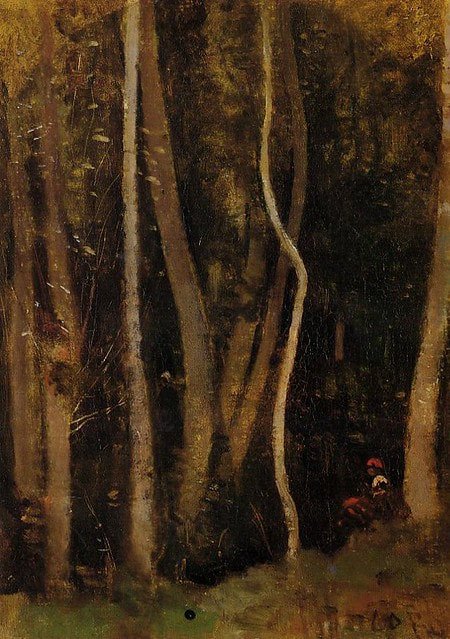

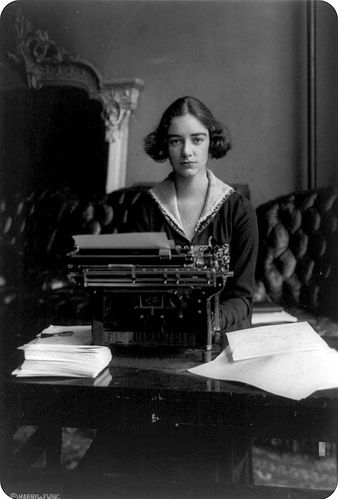

My joy at being a writer has taken another blow. "Never respond to bad reviews." It's like Author 101 - never respond to reviews, ever. It's the dumbest thing an author can do. So, naturally, I am. And Cyberman Ben (the one-star reviewer), if you read this, I'm not pissed off, just sad. See? Look at me being sad... Dear Cyberman Ben. One star? What can I say? Ouch. I’m disappointed you didn’t enjoy my novel. My intention was to visit the near future, explore the world, and have an adventure or two in a way that would engage my brain and potential readers. In that, I’ve failed you. In regards to Sparrow, the “process” for character construction, in case you’re curious, is chaotic. You begin researching the topic, in this case The Future, by studying the past to understand, roughly, where we are now. From that cloud of ideas, phrases, stray thoughts and loose understandings, you extrapolate likely paths and chosen trends you’d like to explore, as they evolve into a hypothetical future. The workload for researching spec-fic, btw, is similar to that of researching for a historical novel in that you’re required to wade through shelves of oral histories, interpretations of events, a host of niche topics, and a lot of unexpected study. You find yourself selecting seedlings from these readings in order to group and plant ideas, facts and connections, letting some grow, pruning others, allowing some to die. During this gardening, plus the 3am musings, and being lost in thought while walking the dogs or washing the dishes, characters emerge from the surrounding fog and forest. At first they’re at the periphery of your vision, unclear and vague. Then, as your research becomes more focused, they tend to make themselves known, and a conversation takes place. Who are you? What do you do? Why do you do it? Where are you from? All this, odd as it may seem, is a two-way interaction – the author isn’t spared a critical interrogation about their motives and agendas. Because all of the characters in The Last Circus on Earth are oppressed in one or more ways, Sparrow, for example, emerged as a furious and determined reaction to the worst kind of oppression – locked-in syndrome (a syndrome I encountered irl when I was a critical care nurse). I found that Sparrow is never passive, uncritical or solely focused on being anyone’s ‘love interest’, Blanco included, as she makes clear on a few occasions. She drives her own life, and this determined selfhood is another aspect of creating and writing characters. At a certain point, as the fictional ensemble grows, evolves and clarifies, the author’s job is less to direct story than it is to herd cats. Then, even this attempt at control is largely abandoned to the point where you feel you’re merely running alongside the characters, taking notes as they all do what they will. In any event, I hope this note from me is of some slight interest to you. I felt I had to write it for myself to get past the hurt. My first dreaded ‘one-star’ review is something I hoped I’d never get, and I can assure you it stings. Experienced authors say to ignore reviews, but when you’ve spent years on a project, narrowly won a publishing deal, and faced the prospect of showing other people – readers – your efforts, it’s genuinely scary wondering what they might think. The horrors of public speaking are over quickly, but a published book is out there forever, and, as staunch as an author needs to be, it’s a part of your deepest self that readers will like or loathe.

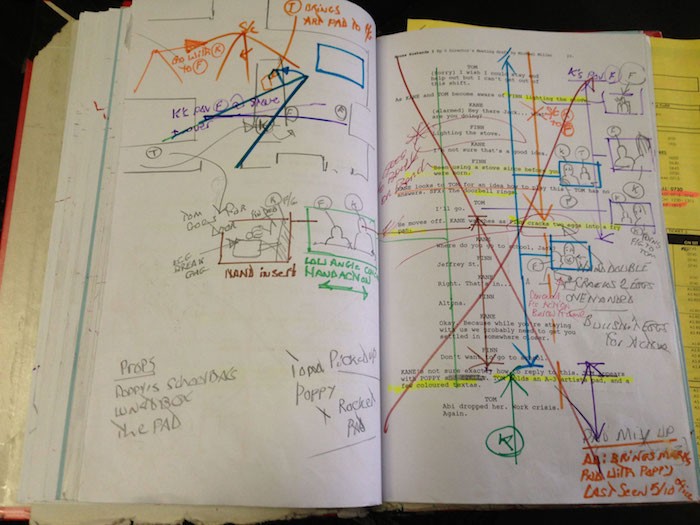

Then, debuting this novel during a pandemic, with no marketing available from my tiny publisher, and covid shutdowns cutting off author interactions with potential readers at festivals and bookshops, The Last Circus on Earth sank like a stone in the ocean of global publishing. As comfort, I promised I’d treat myself to a bottle of the finest Tasmanian whisky (a Nant sherry-cask 40 proof, cheers) when I made enough in royalties. It might take a while before I can afford that first sip. So, for what it’s worth, Sparrow is already asking to lead a sequel in her own right, though Tash is also saying she’s up for it. Blanco just wants to get to Tartika, be a dad, grow vegetables, do whatever it takes to keep his ‘love interest’ happy, and never have another ‘adventure’ again in his life. If another author fails you in the future, as I have failed you, please remember that they tried not to. They risked a lot and worked hard not to let you down, but in the end, for you, the effort was wasted, and their only hope of attracting readers, star ratings, has suffered the consequences. Be kind to that poor author, eh? Last night was the Showcase. All us what done the 12 week Wide Angle's Round 8 End Game challenge - setting ourselves a goal and shooting for the moon, supported all the way by the wonderful Emma, Abi and Robert, got together and celebrated our work. It was satifying and encouraging to hear everyone's stories and struggles. There were outright successes - the stated goals were achieved. There were modified goals that were met with moderate success. Learnings were had and we all seemed genuinely impressed by each others' work. Then I got up to outline my goal, and my plan... ...and then I described what I actually achieved... ...but the joy of learning new skills is what End Game is really all about. Supported professional development is a rare beast in the creative industries, not least because governments couldn't give a shit about 'leftie' creatives starving while Gerry Harvey gets millions in fucking job-keeper. So this End Game opportunity was too good to miss, and the outcome, for all of us, was hugely positive. For what it's worth, I'm now familiar with the depth of my ignorance of writing feature scripts, and can plan my next steps - a revised structure and third draft of the scene breakdown, after which the script will practically *ahem* write itself. So, a shout-out to my fellow alumni, huge respect and gratitude to all at Wide Angle, and a massive thanks to the actors for participating in the read-throughs. Right, now back to work...

In brief.... After reviewing film screenplay-maestro and Wide Angle mentor Robert Watson's notes and telephone conversations, I am staying positive. It's true Robert sent me a TikTok of him burning my first draft scene breakdown out in his backyard, and not pissing on it to put it out, but I can see ways to keep this project standing! I simply need to rewrite it so the characters are interesting, clear and there's a point to every scene - and that the point of the scene is magnificently and instantly obvious to any reader / viewer - all while ensuring the first impressions of my characters are largely on the positive end of the intrigue spectrum. Plus remember to include character arcs for all three characters so they actually go somewhere like real humans rather than stumble through my narrative like Thunderbirds puppets. Simple. In fact I've already started work on the rewrite. Robert did give me the option of just writing the dialogue script rather than laboriously trying to get the scene breakdown to the point where he wasn't inclined to compost it or feed it to his goat - in part because, thanks to me, his goat is getting quite chubby - but no, I'm a martyr for painful learning experiences, which, thanks to an IQ well to the left of the Bell Curve, is a slower process for me than normal people. So, as soon as I've finished my week's work, it's back into the fray, and hope the dogs aren't too upset by the hoarse sobbing noises coming from my workstation every now and then.

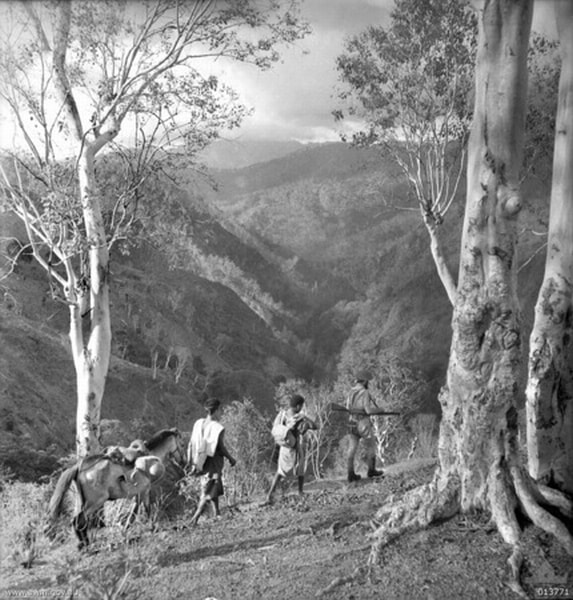

Slainte! So, at this point in the simple task of turning a novel into a feature script, I'm like... The goal of writing an entire feature script in 3 months? So, here's the situation I find myself in. I know my novel backwards. I know my characters, their arcs, and the narrative arc like I know exactly how much alcohol we have left in the house. It's a good, solid, simple story. I'm a third the way through a scene breakdown, identifying the critical events or actions that propel character development or push story. But... When asked to write a logline for the feature script - a sentence, two at most, that sums up the core conflict at the heart of the story - I find I have a problem. The thing I think I'm doing is suddenly, bizarrely, unfamiliar. What is my story? Whose story is it? Explain it simply! Say it in a way that intrigues, and also makes it clear what kind of story it is. Sum the core of it up in a sentence. My response? It-it's a story about a protagonist...although there's three of them. Kinda. I mean...uh... Anyway, my protagonist/s is/are faced with an immensely time-critical life and death situation...not just the war itself, obviously, or the fact the main protagonist is probably going to die, and then there's the whole being-pursued-by-enemy-soldiers aspect... Wait, I'll start again. There's a formula for this, by the way. Protagonist + antagonist + life and death stakes. Simple. Yet, I'm finding myself chest-deep in quicksand trying to summarise the core of the story. I try out some loglines: "Three young men, behind enemy lines, find the road to peace." (Like they find the crossroads and there's a sign with a skull and crossbones pointing left and a smiley face pointing right.) "Every war is a crime, every soldier a criminal." (Yes, that's stolen from Hemingway, and, also yes, it doesn't say anything about my story.) "No one gets the war they signed up for, especially Tassie Eddie." (At least we've got some clues here - some guy called Eddie goes to war and surprise, surprise, the whole King-and-Country thing turns out to be a crock.) "A wounded young Tasmanian soldier, behind enemy lines in Timor, has three days to cross two mountain ranges to reach the last rescue ship. He didn't plan on a needy orphaned kid, or an enemy soldier, helping him get there." (Well that sure af ain't going to fit on the movie poster.) But, and here's the crucial bit - it gets way worse than not being able to write a movie logline. I'm disappearing down a rabbit hole because the feature script I'm trying to build is looking a lot like... But why am I suddenly losing confidence in what, in novel form at least, is a strong, layered, engaging story? I know a feature script is a very different creature, but how can I suggest people see a 'war movie' if I not only don't think it's a war movie, but I wouldn't go out of my way to watch it if it was? I'm not 'into' war stories per se, and I even get tetchy when my long-suffering mentor, Robert Watson, calls it an 'anti-war' movie. For one, almost every contemporary war movie is an 'anti-war' movie, and for another, I have no intention of writing one. It's not about 'war is bad, m'kay?' Is every murder-mystery an 'anti-murder' movie? So if it's not a war movie or an anti-war movie, what the hell is it? An action-adventure? A dramedy? Famous Five Go on an Adventure meets Reservoir Dogs? Hey, what if I leaned on a music soundtrack? Apocalypse Now meets Trainspotting! Yes! Now we're talking...I'll have musical interludes and they'll shed ironic counterpoint to the action and be funny and poignant and also great music and... ...and suddenly, I'm not just trying to write a logline any more. I'm standing in the rain, wondering about my life, clueless. How do I transform a simple idea that works as a novel, into an even simpler single idea that cuts to the core of all the ideas that went into that novel?

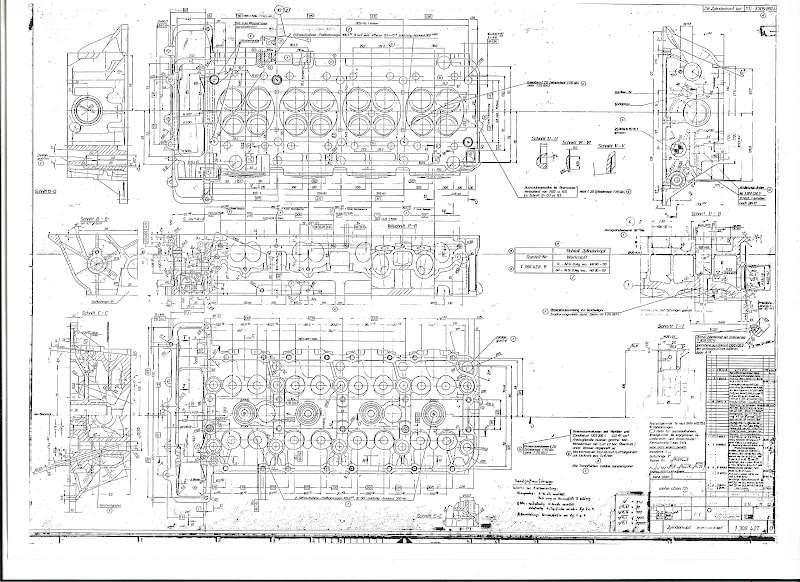

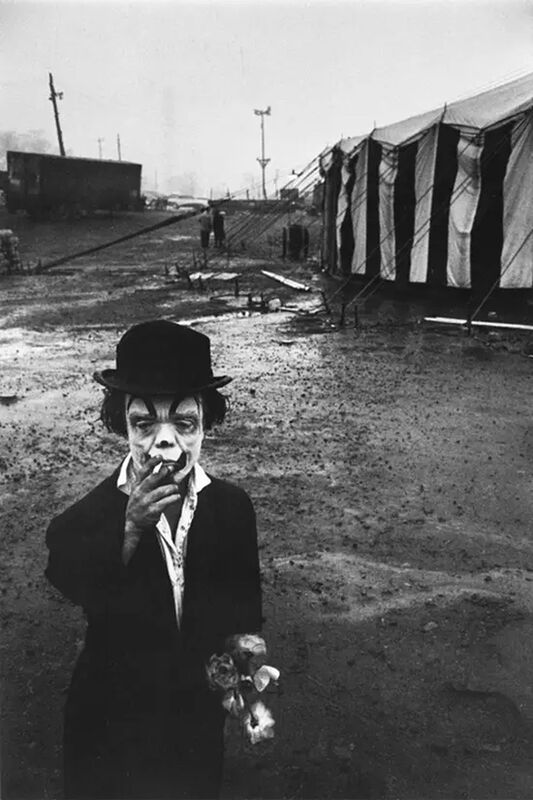

[Photographer: Bruce Davidson / Subject: Jimmy Armstrong - Palisades, NY, 1958] Yeah but nah. If, like me, you've never written a feature script, only novels, then, like me, you might be naive about how different they are. I assumed I'd take the 'good bits' and critical moments from my edited MS - what I thought was a straightforward coming-of-age-in-a-time-of-conflict story - throw them into a scene breakdown (a paragraph thumb-nailing what happens in each scene), and then write the dialogue script. Nope. Typewriter says 'no'. Turns out, even though I'm a television scriptwriter, I apparently learned nothing by watching hundreds of films and am largely clueless about building a feature script. It's the difference between living with bookshelves all one's life, then actually constructing one. It requires an understanding of new tools, and and an attention to detail that a lazy novelist like myself finds difficult. All the subtext and nuance in your deathless prose means zero when you have to communicate ideas and emotions visually - often in an entirely obvious way. You need to write the scene in which the viewer actually hears a character say 'I love you', and sees the kiss. And so it was that my mentor, the estimable, Robert Watson, received my first draft of a scene breakdown for the opening sequence, with a dismay he graciously hid behind some patient advice to try writing the same sequence as script. This I did... ...only to achieve the same response. I'd completely failed to introduce the characters in a way that provided viewers with understanding, empathy and insight. Waaat...? In a lengthy phone call, Robert guided me toward understanding the difference between writing a descriptive passage and creating visual action that tells story. It seems so obvious, I know, but the subtleties of prose have to be tossed, the clever novelist expansion of plot and character has to be kicked aside, the narrative has to be pulled apart and sorted to find workable components - or write new story to make all the bits work as story. I need to write new material to show stuff happening, and engage viewers much earlier. My novel on which this is based, is to be viewed as a dumpster of building materials, some of which are junk and some of which are useful. I'll be honest - it's hard. Three months to write a feature script in between my working days?

I got my story. Where do I begin working out what to put in a script? What process do I use? Wide Angle hooked me up with Robert Watson, screenwriter, screenplay analyst, editor, teacher, historian, philosopher and, oh yeah, he paints landscapes in his spare time. We met and he clued me in to the crucial equations of novel conversion and screenplay structure. We talked through starting and end points. In the case of my story, The Sparrow, it begins with one of my three main characters being shot. His body goes flying back and down a small cliff and yada yada, things get worse until the end. Simple. So, what do I do first? Write a list of the main events - the large and small but crucial moments of the physical and emotional journey. List? I can do a list, damn it! Bullet-points? You got it! Then I have to sift the list. Each item on the list is a key moment of interaction between the characters and their environments, one which advances plot and character development in that one moment. Sifting the list means looking for items that might be a repeat or a non-essential moment, or simply less interesting, then taking that item out. What's left can be large or small - from death to disappointment - but it has to be critical to story and character arcs. Is it lifting the emotional drivers of the story to a higher pitch? Keep it. Done that? Good. Take a rest, and maybe tidy the desk. Next steps, consult with Robert, then put scene headings on the remaining items. Then write a brief outline of what happens in that scene - a scene breakdown. Then the easy bit, write the dialogue. How hard can it be? Again, big shout-out to Abi and Emma at Wide Angle for connecting me with Robert. Slainte!

Just won a place in Round 8 of Wide Angle's End Game programme! For the win! It's a real leg-up to have this level of support pushing the first draft of a project through - in this case turning a historical novel manuscript into a feature script. While I'm familiar with television scriptwriting, I'm painfully aware how big a set of challenges I now face. Turning this... ...into this... ...is the challenge. It's one thing to have written the narrative of an unlikely friendship between a Timorese criado, a young Tasmanian commando, and a Japanese defector during the Pacific War; it's another set of challenges to turn that into a feature script - a story which will be told by actors, director and cinematographer. When End Game kicks off, all of us in it will have 12 weeks to deliver a project. *gulp* But, hey, how hard can it be? Big shout-out and thanks to Abi and Emma at Wide Angle for the opportunity, and [waving] hi to my fellow Round 8 End Gamers.

In most forms of storytelling, character is everything. Even narratives we'd describe as plot-driven only work - are memorable, compelling, etc - when we emotionally engage with the characters. Screenwriters are more sensitive to this reality because they are largely collaborative storytellers working in an industry which has a commercial imperative - everything has to work. That doesn't limit us in the stories we tell, as Anthony Mullins, Australian screenwriter and novelist, points out in his new book, Beyond the Hero's Journey - A Screenwriting Guide For When You Have A Different Story To Tell There are many books that guide storytellers in this era, for screen and off, including those who reference the standard 'hero's journey' and 'three-act' structure. Including those approaches, Mullins' book is particularly useful, not least because I'd recommend it for writers in any genre or format. It's not a how-to, nor is it painfully academic or require wall-covering plot analysis for your WIP. Screenwriters focus on character and their arcs. Mullins points to how that process plays out in a diverse sampling of feature films, and does so simply, succinctly and engagingly. I recommend it. So, if you're a writer, with a WIP, and interested in reading a short review about Beyond Hero's, hit the link to the review at Tasmanian Times.

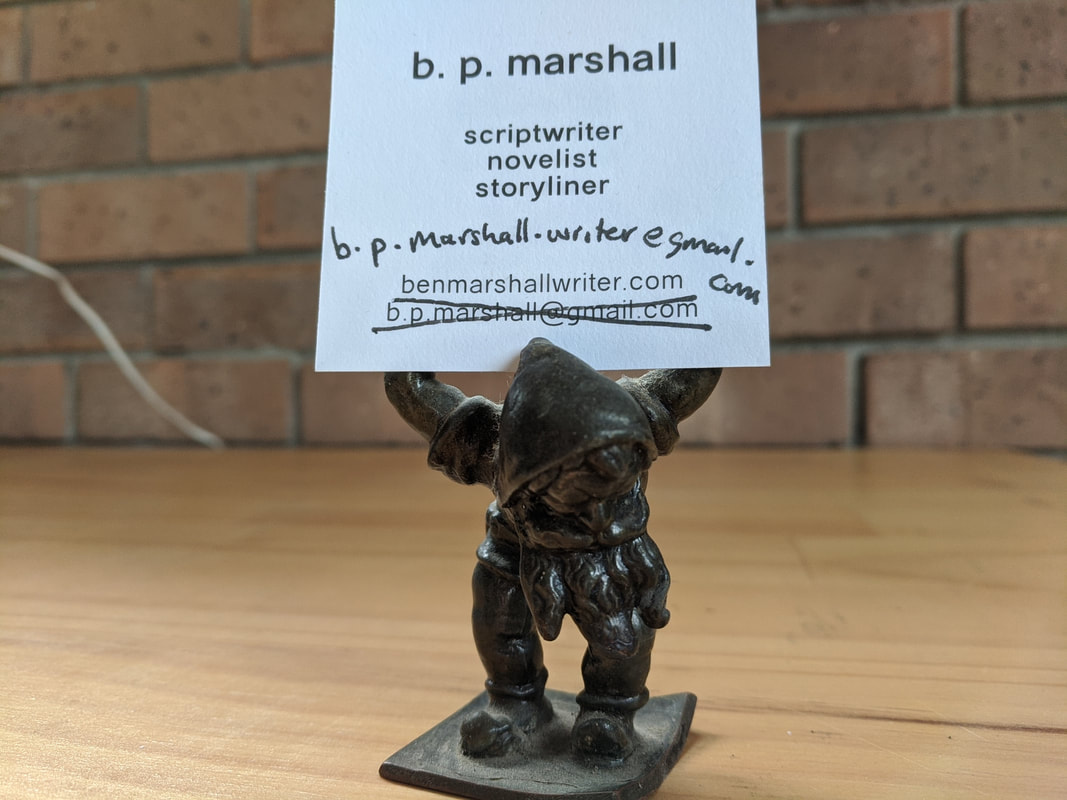

Pro tip: after having your business card printed, check the contact details are correct or else, as in my case, somewhere in the world, someone else with your name, whom you've never met, is being contacted about writing a book they have probably never heard of. If anyone contacts [email protected] because they have one of THESE business cards... ...they will not be contacting me. They will be contacting another b.p.marshall whose life and existence I can only imagine. Perhaps this other b.p.marshall has also written a novel. Perhaps we'd have much in common. Perhaps, even, they too had a business card made up in the vague belief that, when attending a writers' festival, a writer should have cards to hand out - to whom and for what purpose they can only dimly imagine. Perhaps, even more incredibly, my b.p.marshall doppelganger also had the wrong email address printed on their business card. We'd laugh and become the best of friends... Or, as has actually happened, I've emailed a complete stranger explaining the whole thing... ...making it clear that I'm the idiot and that any multi-million dollar feature film offers should instead go to THIS carefully curated correct email address... To my doppelganger b.p.marshall, I apologise unconditionally... Unless, tempted by the multi-million dollar offer from a major film studio, you are, at this very moment, writing a script using my novel as template. In which case your evil genius impresses the hell out of me. Well played b.p., well played.

|

Reviews & stuff

Archives

July 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed