|

I chose a circus freak show as the world for The Pricking of Thumbs for two reasons - Ray Bradbury’s 1960’s novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Tod Browning’s 1932 ground-breaking film, Freaks. Something Wicked elicits mystery and horror. Freaks elicits horror and pity. The book sends chills because we struggle to imagine the horrors. The film gives us nightmares because we see the horrors are real. If you’ve seen it, you’ll remember your reactions to it long after you forgot the plot was a thwarted-love story. The freaks in the film were borrowed from various travelling circuses and sideshows of the time. Browning had worked as a carney and his good nature allowed us to see people whose physical appearance and mental attributes shock us. It’s only a mild spoiler-alert to mention the real freaks of the movie aren’t the ones with disabilities. Digression one: I broke my leg one time, and because I was living in the tropics, the second cast was replaced with a moulded plastic brace I could take on and off. The climate was hot so I wore shorts, leaving the brace exposed. What reaction would you expect I’d get from people in the street? You’d probably expect, say, concern or sympathy plus a few wtf looks, right? I got them alright, but what surprised me – what shocked me - were the occasional looks of disgust and horror from people. Micro-expressions mostly, but they were there. Never from kids, rarely from men, mostly from young to middle-aged women – my age at the time. If I copped disgust for a damaged leg, what do people with a pronounced physical disability get? My point here is that we react in a visceral way when we see freaks. A deformed human makes our minds flip between repugnance and compassion. On a deeper level it can also inspire ontological questions. And that’s why freak shows did so well before the advent of film and television. As we react to a man with no limbs who can roll, light and smoke a cigarette, we’re relieved we aren’t like him, but we fear and resent him because he challenges the idea of a fair and compassionate God. And where there is fear, there is hate. It’s one of the reasons Freaks was banned for decades and the maker forced to change the ending. My freaks exist in the tough world of the post-collapse future. More like the Great Depression than The Road, it’s a world that uses what resources it can from the technological past while returning to a semi-medievalised world-view. It’s less a dystopian vision than it is humans returning to a kind of default state. All of which brings me to my theory. Digression two: My last novel was set in the seventeenth century. I wanted to explore a world where the medieval met the Age of Reason because, technology aside, I think that’s where humans stopped evolving intellectually. Science aside, we’re still fearful, superstitious and quick to lash out at difference. We haven’t really advanced beyond the thought that if we can’t understand something, God did it, so we don’t need to strain our brains a second longer thinking about it or asking intelligent questions. Anyway, the new novel, The Pricking of Thumbs, is my chance to explore what emerges from the rubble, and what our default world-view is. I don’t know the answers to those questions yet – I’m only a hundred and twenty pages in, so there’s a lot of looking around my dangerous world before I suss it. Still, I have good companions - freaks take nothing for granted and are tougher than I’ll ever be.

1 Comment

Adult fiction, western-noir, a first-person POV tale of redemption. Two murderers for hire travel to the West coast to make a hit for their boss and it all goes wrong, along the way and on the hit itself. All told in low tones from the brother lowest in the pecking order.

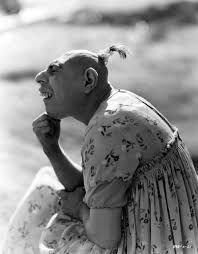

What I learned: telling a story in mild dialect is effective to establish time, place, mood and character, as is a self-aware unreliable narrator in expressing best those emotions that link the reader to the characters. While the events are a roller-coaster action-wise, they're muted by the voice of the narrator, who is depressed and fed-up with his life. This doesn't, however, mute the engagement I felt with him and the story. In fact the self-deprecating earthiness of the narrator grounds the tale. It feels more real. I like. I’m a full time script-writer for television. Which, stated baldly like that, sounds like I’m attending a Writers’ Anonymous meeting and am about to unload my tragic back story. I’m not. But while I’m a pro with scripts – describing action, structuring scenes and writing dialogue – I’m an amateur when it comes to short story and novel writing. Since moving off a property two years ago, I’ve had time to explore this other area of writing and pretend there was a chance I might one day be published. This admission will, to those aware of the current state of the publishing industry, indicate that I’m an optimist by nature, which will, to those familiar with contemporary psychology, indicate that I’m hopelessly unrealistic. That said, my impressions of the writing game so far show that a level of blithe ignorance and dogged obsession are the most useful tools to advance one’s fantasies of becoming a ‘proper writer’. The motives for wishing such a pointless outcome to come about range from a vague desire to attract admiration from others similar to that I gave to the loved writers of my youth, to a murkier desire to show off to those who never thought I’d amount to much. I’m talking about my parents, of course and, as mine are both dead, I feel my less murky motives are similar to geezers who fill their attics with model trains and miniature landscapes. I want to build a world where I, and others, can lose ourselves and re-find ourselves. Writing soap opera, as I do, requires me to locate and reveal the emotional truth of a scene. Those who scoff at soap because of its shonky production values, hammy acting and stilted dialogue are welcome to do so, btw, but should be aware that those who invest in a soapie are emotionally engaged with it, just as you are with a serial drama you would choose not to scoff at like, say, The Wire, The Slap, The Straits or The Simpsons. The fundamental difference between, say, Neighbours and The Wire is merely money and time. The similarity - that which we viewers draw sustenance from - is the emotional truths revealed in them. A good story well told is what all writers seek to achieve, but we often stumble when we mistake plot for story. Plot is a series of events occurring over time. Story is what happens to the characters within that framing, and is the bit we really care about. A feature film can take a year to write and make, often much longer, costs millions and lasts for a couple of hours. A week of soap opera takes a week to write and make, on a shoestring – hence the production values. But while a feature film might have a couple of plots to tell its story, a week of soap will contain up to a dozen storylines. Television storyliners produce plot and story at a rate you can’t imagine, and they do it hour after hour, week after week, year after year. In this grinding of mental gears, brains get worn and sloppy, and one of the first things to go wrong is the creation of characters. When things are going wrong, characters begin to be written up as a physical description and a series of personality traits. Here, I’ll make one up for you. ‘John is a good-looking twenty-something defence lawyer with a passion for criminal law. A risk-taker by nature, he often takes unwinnable cases and loves to throw himself into extreme sports. His good looks and confidence endear him to women of every age, though John is yet to overcome the hurt of losing the great love of his life, Lucy, in a car crash six months ago.’ That was an example of a typical character thumbnail in television, and it’s an example of absolute crap. It tells me nothing about what gets him out of bed in the morning or what his real drives are. Sloppy character creation will give a character motives like ‘he or she seeks fame, money, success or love’. We all aspire to some or all of those things so it doesn’t help understand the character. It’s the ‘why’ the character aspires to any of those things that counts. Let’s tackle John again. ‘John is a twenty-something defence lawyer. His father was a High Court judge, was almost completely absent from John’s life, only interacted with his son to urge him to higher marks or put him down for anything less than an A+, and secretly suspected John was not his biological son. His mother was a self-obsessed academic and trustee of several charities, who had John by accident late in life. Last year John was driving the car when he crashed and killed the girl he’d just proposed to.’ Okay, it’s not Tolstoy but it’s better - you can see where I’m coming from. The crucial thing for me in telling stories is character. The crucial thing for me with character is knowing exactly what they’d do in any given situation because of who and what they are. Character is story. I plot novels like a bank robbery. Get a plan, assemble a crew, assign them their jobs, then hit the bank, hard and fast – in, out, no-one gets hurt. Then, inevitably, someone turns left instead of right and everything goes horribly wrong. My current protagonist, Rousse, is an orphan indentured into a travelling circus and freak show, one that offers the usual entertainments but which also engages in a series of much more profitable, and violent, crimes. Rousse wants to escape. He hates the circus, he hates what he does, he hates those that control his every move, he hates himself. He’s fed up with his life, the brutality, the pain and the guilt. With few safe prospects outside the circus, he’s close to topping himself. He is, in other words, a character who should do what he’s told and go where you want him to. Unfortunately, the bugger’s developed the kind of bravery that comes with having no hope. Which means that when I suggest he not mention various plot points to the other members of the circus for the purposes of dramatic tension, he ignores me and tells them anyway. His whole life is dramatic tension and pain, so keeping secrets to reveal later as new turning points strikes him as pointless. Another case in point. Sparrow. She’s been kidnapped and had her brain operated on by the Professore - a sociopathic Mengele type - who converts girls to Nightingales, freaks who can sing like angels and do nothing else. Lobotomised, they are cared for by the other freaks, and are objects of mingled pity and wonder as the only parts of their brains left functioning are connected to their vocal cords. But the Professore’s neurosurgery isn’t perfect, and when Sparrow emerges from her locked-in syndrome, the personality that emerges from this delicate singing angel emerges less like a butterfly from a chrysalis than a bull entering a china shop just before closing late on Christmas eve. Can I suggest she go easy on Rousse, bearing in mind his depressive and pre-suicidal inclinations? Can I urge her to some restraint considering his self-loathing? Can I bollocks. No, she’s been stuck inside her brain watching and learning and falling in love and she’s buggered if she’s going to wait to tell Rousse how she feels. Can I stop her going to the one person she shouldn’t go near, let alone make demands of - the sinister and violent circus owner Mister Splinter? Can I suggest she not get a sniper rifle and climb on the roof of a moving trailer to take out a helicopter in the middle of a fire-fight so she can protect Rousse? You can see what I’m dealing with here. The three-act structure means nothing to these people. I’m trying to rob a bank – I mean, write a novel, and they’re trying to live their lives and find meaning and happiness. I find myself relegated to reportage as this mad troupe fight their way across Europe. First Campbell Newman ditches the Premier’s Literary Awards – letting me know that my work is neither valued nor wanted, then my characters take over my manuscript. Plotting? Ha! Is the story told by a bald, hunchback female dwarf, crippled not by her physical condition as much as she is by love and the ties that bind. Born into a tight family of circus freaks, deliberately being manufactured by their ‘normal’ parents via the consumption of poisons during pregnancy, the story is of the dissolution of the family. What I learned was that love, as one of the great themes, can still be presented in a fresh way. In the twisted maelstrom of the circus and the cult it becomes due to her limbless brother’s megalomania, love is central to everything. Realising that theme completes the reader’s experience of the story. Meandering with a broken, non-linear narrative, it also paints the world of the circus in broad brush strokes, with the reader left to fill in the many gaps – not a conventional or ‘proper’ approach but, with just the occasional finer strokes illuminating one or another aspect, it works.

Angelmaker taught me you can have a story that lurches about like a skateboarder on acid wearing high heels eating one of those gourmet burgers that are so unfeasibly overfilled you realise it would be easier for everyone if you just ate the thing standing in a bin that could catch all the stuff that rains out the sides…and still get great Amazon reviews. Oddball, quirky, steampunkish, barking mad and colourful, the characters are as implausible as the story but when you have this much indulgent fun writing it, as clearly Harkaway has, it’s a fun read, even to serious young insects like myself. Maybe the other lesson is there is a publisher for every kind of book, even messy ones like Angelmaker. If I'd been his editor I would've killed him with an ornate Edwardian dresser with secret drawers full of dusty letters in an obscure dialect found only in Eastern Kazakhstan and a single key cunningly manufactured without a lock to fit it.

Probably the one thing you don't do when you've finally gained that most valuable and rare opportunity - a face-to-face meeting with a major publisher's editor - is being late. The other thing you should avoid is obliging the person who set up the meeting to come and drag you out of a talk by a forensic psychologist to attend. The final thing not to do would be 'explaining' you were late because you were so interested in the talk you just got dragged out of - because that would be like saying 'sorry, but I was doing something interesting and forgot all about meeting with you'.

So, I think we're quite clear about not doing any or all of those things. Only an idiot would behave in such a way. And, yes, that's exactly what I did on the weekend at WriteFest in Bundaberg to the charming and courteous Rachael Donovan of Allen and Unwin. We met to discuss the finer points of my submission of The Pyrate's Sonne to U&W, and for Rachael to give some impressions of the first fifty pages of the MS. She was kind, generous and positive. On the down side, she felt the word-count was too high, thought the book was for a younger age group because the protagonist is fourteen years old, and was gently dismayed by the racism. Tricky. All the characters in The Pyrate's Sonne are racist as. Even the young hero. He doesn't think Jews eat babies as some of his crew do, but he's quietly convinced that seventeenth century Englishmen are the pinnacle of God's creation, and all other races inferior to them. As you do. The trouble is, apparently, that some parents, teachers and librarians feel that if a character expresses an opinion, it's also the opinion of the author. You and I might be able to distinguish between a fictional characters' words and their writer's thematic discourse on, say, racism, but not so others. So, a valuable insight into the real world, and one I'm truly grateful for. Sandy and Cherie Curtis, and the entire Bundaberg Writers' Club, provided this opportunity plus a range of talks on a various topics to help us unpublished writers take another step forward on the learning curve. The BWC are a sweet bunch of people who made me feel part of the family. I can only suggest the reader consider the annual WriteFest a must-do on their writer's calendar. True Love, the short film by Robert Braiden and Simon Toy, written by me, has been wandering the globe, from one indie film festival to another. And now the NYC PictureStart Film Festival. New York! Just like I pictured it...

Steve Rossiter – Australian Literary Review:

You're a full-time TV writer, who has written for shows such as Neighbours and Shortland Street, as well as a fiction writer. What advantages or disadvantages does one form of writing have over the other? Do you consider the differences to be small in comparison to the shared storytelling capacity of TV writing and written fiction? Ben Marshall: The obvious advantage is that television pays my mortgage. Fiction hasn’t yet coughed up a bean. I haven’t been chasing the fiction dollar, mainly because I’m too busy trying to stay afloat as a freelance writer, a career that means never saying ‘no’ to a gig. That said, the advantages of writing to spec are that the constraints on what I can and can’t write are clear. Some bridle at being bridled by storylines, arguing perhaps that they limit creative problem-solving. I don’t think this way. Constraints focus my efforts toward creatively problem-solving to achieve the goal, which is bringing out the emotional truth of any given scene to produce emotions in the viewer. Or, in terms more familiar to Gruen Transfer viewers, I keep people from switching channels and missing out on the ad breaks that pay for everything. The disadvantages are network censorship, the production-line nature of television story creation, time-slot limitations, and the fact that people get huffy if you make fun of minorities, those with different ethnic backgrounds or anyone with a speech defect. Consequently, the advantages of fiction, and being unpublished, are that I can write any feckin’ thing that tickles my fanny at any particular moment. My books are full of racist, sexist and thoroughly un-PC types who run about causing trouble and being offensive on almost every level. Their honesty and openness is refreshing. Steve: When asked in an interview who your favourite Neighbours characters to write for were, you wrote: "Any well-constructed, clearly defined character – that is, one with strong internal conflict built in from scratch – is a joy to write." What makes a strong internal conflict, which is built into a character, as opposed to a weak internal conflict or one, which is not truly built into the character? Ben: There are many ways to construct character but basic questions need to be applied to any construct to test them. Are they interesting enough to watch or read about? If not, why not? What are their drives and what’s driving them? What are the strengths that will enable them to succeed and what are their weaknesses or conflicting drives that will almost certainly ensure they fail? To hope a protagonist succeeds one must also fear he or she will fail. Before that though, we must care for them. We can only care for them if we empathise with them. To empathise with them we must understand them. To do that we must see ourselves as part of who they are. So examples of driven characters with inbuilt obstacles might include, off the top of my head, a mother of three lovely children who is immobilised by grief for her dead husband, a lonely GP who is also a misanthrope, a heavily-mortgaged professor of post-modern studies who has early-onset Alzheimer’s, a prosecution lawyer who is also a heroin addict, a bi-polar school teacher, an athlete with an overbearing mother, an introverted young businessman working for his overwhelmingly successful and dictatorial father. (In case you regard parents as external obstacles, btw, they aren’t – our parents are inside us like the alien inside Ripley.) Poorly constructed characters are uninteresting because they’re superficial – a mere physical description with a few personality traits attached to them – therefore whatever situation they engage in we don’t ‘know’ or understand the character enough to care much about the outcome. Steve: You've written : "The crucial thing for me with character is knowing exactly what they’d do in any given situation because of who and what they are. Bottom line? Character = story." How would you describe your approach to developing a story in keeping with a character's personality? Ben: While I definitely do my research, my approach is instinctive and chaotic. (Chaos as a form of order like, say, a drunkard’s walk.) Once the characters begin to emerge from the forest of thoughts, every subsequent action they take further reveals their character. Then, often within the first chapter, it becomes a matter of trying to keep up with the buggers as they race about trying to achieve their aims, while being crippled by internal obstacles and confronted by external issues. I tend to get a crew together and launch into an interesting situation that I have no idea how to resolve. It’s up to the characters to work within their means to achieve some sort of resolution. I love them, wish them well, provide what help I can, but in the end it’s up to them. Steve: TV shows and the vast majority of written fiction tend to be written in scenes. What tends to make for a well-crafted scene for TV and/or written fiction? Ben: Paint a picture, create tension, make the viewer / reader want to know what happens next. Steve: Your current work in process is set amongst a travelling circus in a future Europe. How has this compared to writing a story in a setting like contemporary suburban Australia or New Zealand? Ben: Those in my freak show can’t hide the fact that they’re freaks. Those who inhabit suburban Australia or New Zealand are able to pretend otherwise. Steve: What is one of your favourite novels that you have read in the past year or two and why? Ben: In terms of what blew me away, I read Pippi Longstocking for the first time when I bought a copy for my wife. Pippi totally rocks. She just does not give a shit and I love her. The Awesome Must-Read Award for character portrayals would go to Homicide by David Simon except it’s not a novel. Otherwise I’d have to say that my rereading of Catch 22 proved, again, that it makes most other novels redundant. I don’t know why I bother. Steve: What is a TV show from recent years you consider to have well crafted characters/stories and what makes them work so well? Ben: The Wire. Series 1-5. The particular genius of character creation here comes from the lead writer, David Simon (same guy who wrote Homicide) embedding himself for an entire year in the Philly homicide squad. The Wire I often call ‘television for grown-ups’ because it requires the viewer to think. The characters are revealed slowly, and unfold themselves over a period of many episodes, the complexity growing as we get to know them in the same way we would anyone we spent enough time with. I think I used the word ‘genius’ already. Treme is another good David Simon series. Steve: What kinds of fiction did you read as a child/teenager and do you have some standout favourites? Ben: Ray Bradbury, Lewis Carroll, Mark Twain, Rosemary Sutcliffe, Alan Garner, Douglas Adams, Joseph Heller, Hunter S. Thompson, Cervantes, Conan Doyle and P.G. Wodehouse. Steve: If you could bring one fiction author back from the dead for one day, for the sole purpose of chatting about fiction, who would you choose and why? Ben: It’s a toss-up between asking Lewis Carroll if he was privately aware of the satirical aspects of his Alice books or having a beer with Mark Twain and listening to anything he had to say on the subject. I think I’ll go with the beer. YA/cross-over novel. Coming-of-age / small town mystery, set in Australia during the sixties. A good example of a good story told well. What I learned: there are twists you’ll probably see coming but sometimes that doesn’t matter if you’ve bought into the emotional journey, which I did. Any flaws were few, small and not worth mentioning. I enjoyed it.

|

Reviews & stuff

Archives

July 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed