|

“It’s just a story.”

This is how Judith self-deprecatingly referred to her new novel after I complained my wife had grabbed it and, before I could get to it, started reading. My wife - a fast thinker but a slow reader - wolfed down Thicker Than Water. I watched her find time to read when normally she wouldn’t bother. A good sign. When it was finally my turn, I was drawn into the story. A young woman, Lucy, born from a rape, sets out to avenge her mother. The man she seeks, her biological father, lives on the other side of the planet, is Italian, has a loving family, a business under threat from mafiosi, is well-regarded, and has everything to lose from having his crime exposed. All power lies in Lucy’s hands, and the main driver of the narrative is how she uses it. The setting moves from Victoria, Australia to Southern Italy, both familiar to the author. Colquhoun’s dialogue is pitch-perfect, and her naturalistic prose is a relaxed yet taut mix of show-and-tell that works well to propel story to just the right pace with just the right amount of context. Any exposition is brief and insightful. I never felt a sense of the authorial voice intruding. The portrayal of Southern Italy is rich without being verbose. Colquhoun paints a picture well. Crisp, clean writing. I couldn’t fault this charming story – I was hooked, didn’t know what was going to happen next, and kept reading to find out. It may seem like faint praise to any non-writers, but TTW is also beautifully and efficiently structured and edited. And well proofed. I found one misspelling. Did I mention My Asperger’s side? Despite the dark crime that is the seed of TTW, I’d describe this as a warm, humane and honest portrayal of human behaviour. “Just a story”? Sure, but one I have no trouble saying I enjoyed a great deal. Recommended! *Disclosure: Judith is a friend and colleague. That said, I paid for my copy, and, trust me here - if Thicker Than Water had turned out to be a dud, I’d have slipped my hands in my pockets and walked away, whistling softly, never writing this review and hoping Jude never asked what I thought of it. Buy it from Black Pepper Publishing http://blackpepperpublishing.com/colquhounthi.html

0 Comments

At the vet dog shelter, in a room stinking of fresh puppy shit, the Australian Kelpie-cross puppies who made all the stink and mess, are a mad scramble of canine characters. Out of that litter of seven or eight gambols one pup, not too manic and not too needy. He comes to me and smiles.

At home, Daisy, now five or six years old, doesn’t care too much for him, but we do. Again the routine of mopping up messes and training, but this one, whom we call Spud, is a sleek and shining black dog, invisible in the shadows, who wants to help, wants to do the right thing, even when his irrepressible high spirits get the better of him. Fences are again an issue, especially as he can squeeze his bendy, skinny, flexible little body through all manner of tight spaces to get out and explore the world. Then he learns to jump, making the crap temporary fences redundant, and the construction of higher more solid fences the priority. Out in the sun, he runs, gleeful, through the paddocks, chasing the alpacas until they, protecting themselves and the ewes, form an arrowhead and start backing him up, at which point he looks sheepish and ready to talk his way out. He runs to the high ground to watch over us, his Kelpie genes kicking in. Bounding and bouncing through the grass when it gets high. Swimming in the dam with who knows how many tiger snakes. Rustling through the reeds, joyful face appearing. Fear of the car until the first trip to the park, and from then on a mad paint-scratching scrabble to get in the back seat and go anywhere, head out, long tongue flapping, barking. At the park, working off that boundless energy, I use the ball-thrower to fling the ball as far as it can go, and set that black lightning streaking after it. Bounce, leap, mid-air catch. In the car after, soaking through towels, Spud, muddy and wet, tongue hanging, beaming and barking at white trucks and cars. Only the white ones. Loud as a bastard. Breakfast sees that little face appear, hope writ large, joyful if there’s a slurp of milk in a bowl. Always happy, always wanting to have fun and do the right thing. A gentleman, ready to share anything he has, be it a ball, a bone, or a bowl of food. Learning to ‘leave’, the crucial command to ensure he’d step away from snakes. Sit, stay, lie down, find it, this way, okay let’s go, okay – what time is it? All simple instructions he’s happy to learn and do. Sleeping on his mat, almost steaming by the fire, or curled up on the couch, head on our lap, eyes open and drinking in our expressions. After dinner Spud’s the mobile fat-trap, doing first-stage dish licking with earnest gusto, tongue flapping like a wet rag, determined to get every last skerrick. The joy of the long drive to Queensland, stopping at footy ovals all the way, losing the collar out the window with the new Queensland rego tags. Arrival, and the joy of the new lake, of chasing the ball, the leaping, the grace, the on-shore leap and the off-shore landing. The final paws-up pounce on the ball, the big splash. Skimming the ball across the flat sheltered water of Hatch’s Bight, Spud bounding in the, to him, chest deep water, the pounce and then the reluctant but generally gracious handing over to the slower bully Daisy, then forced to watch her glacially slow return to shore with wistful eyes – a hiatus to the fun, but, later, the chewing of dead tree roots beside her in companionable work. Spud’s favourite thing - his party trick; hiding behind a tree or anything, throwing the ball out from his hiding place where we can find it and throw it. At which point he emerges – surprise! – and chases and catches. That mischievous face, expectant and smiling, half-hidden behind a tree, in bushes, behind one of us. Running off in the State forest after a kangaroo. Searching to find him again. The yawning fear we’d never find him. Twice. And then never again in that forest. Always at our sides as we worked, outside or in. That, or lying by the fire or in the sun close by. Then, after a rest, that bright open face and smile appears with the implicit suggestion of a trip outside to play with the ball. Wouldn’t that be awesome? For a skinny black dog, he has a bark that will raise the dead, a Baskervillian boom that, unannounced, sends me flying upright out of my chair. The joy of the beach. The dog beaches at Sunshine and Coolum – dog heaven, no leads, no territories, no hassles. Spud racing through the park to the beach to wait for the first throw, pounding along the hard packed sand or splashing into the smaller waves. It’s all about the chase, the bounce, the catch, preferably mid-air. Tireless chasing, running and catching. Then, after, sinking down onto his side of the back seat to rest, or sit up and rest his head on my driving shoulder to look forward, be close, and get the open driver’s window breeze. Appearing in my doorway, he looks like a cartoon dog sometimes; the bright whites of his eyes with those beautiful amber irises, tail up, the smile of mischief and readiness. Every half hour – let’s go! A short run next door will do; anything together. Lying on the couch, head in Brenda’s lap, looking at me as if to say life could not possibly get any better than this. An almost overwhelmed smile of complicity in such joy; a sharing of his joy. That awful 2011 Christmas. A week before Christmas, Spud is ill, cause unknown. Within days, it’s clear he’s dying. Visiting the vet, Spud, as always, is a happy, gracious visitor, accepting, tolerant, generous and brave. The drug regime works to an extent but as time goes by the diagnosis emerges. He’s probably not going to get better, and we can only control symptoms. Still, the possibility of improvement spurs us to do all we can. For the next eighteen months, the slow, incremental decline. Never in pain or distress, always happy unless weaned too quickly off the prednisolone. A process of learning what drugs and diet helps most to keep his tail wagging. In the end, that’s all that matters. If the tail wags, then we can do no more. Walks become slower, less frequent, shorter. Ball play is still fun, but no longer the aerial acrobatics, only little catches. It doesn’t matter to Spud, who only cares to play with us, sharing the ball equally between us. I take no chances with pain, and soon painkillers, three times a day, are part of the regime. The pressure sores begin, and Brenda makes padded pants and a harness arrangement that allows him to sleep, infuriatingly to us, on his side on the hard floor. Keeping cool is crucial as his metabolism burns out of control. The air conditioner is bought. Would we have bought one if not for Spud? Mats are everywhere. Places to rest his increasingly skinny bones are there when he needs them, dressings are twice a day, play time ten times or however often he wants. After the big 2012 ‘low pressure system not quite a cyclone’ storm, the next door’s half-collapsed grevillea makes a wonderful green, leafy place to hide, and throw the ball out so I can give him the joy of springing forth out of hiding to reclaim it, then throw it back to me. That mischievous smile, those bright eyes, peering out, waiting for me to engage. Always sharing joy and love. And always, when there is any kind of food preparation in the kitchen, Spud is there, patiently lying on precisely that area of floor in a direct line between the counter and the stove. He's so trusting he never fears he’ll be trodden on. So we never tread on him. Dropping down on a wooden floor, he sounds like a sack of logs when he collapses in front of the fire, or onto a cool floor in summer. A year later, there’s not a single day goes by I don’t remember that sweet face, that big heart, the dozens of moments in every day he brought us joy. ‘Just a dog’. Don’t use that expression around me. Ever. Rest in peace, my sweet boy. The premise: a Mars mission is forced to abandon the planet during a storm. In the chaos, one of their number, Watney, is killed. They don't even have time to bury him before they take off. Except Watney's not dead.

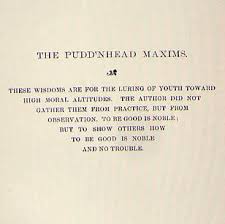

With no hope of survival beyond the limit of his food, water and air supply, our hero is doomed to die. And so the story begins. Weir has taken a nice simple premise and played it out with a Hollywood scattering of bit players and an engaging heroic protagonist. It feels like it's either already in script form, or is about to be made into one, but I'm not criticising that at all – either way is a terrific way to construct a story. The narrative is in plain, folksy language, and is a well-paced, engaging read with plenty of twists of the whatever-can-go-wrong, does-go-wrong sort. It’s a popular novel, especially in the US, and the Amazon reviews quickly piled up to sub-orbital heights. A big well-done-that-man to Andy Weir. It’s mostly in diary form, which gives it an engaging first person feel, allowing us in to Watney’s stoic good humour as he tackles the slings and arrows. Overall, Watney was a little too stoic for me – just a touch of total despair, wretched, bowel-loosening fear and utter misery would, I feel, been appropriate to the context and enhanced his characterisation. Speaking of characters, I liked them. I liked them all. Gosh darn it - they were so damn nice, especially that swell kid who spotted the crucial satellite shots, and whose grumpy good humour added contrast to her gruff Right Stuff bosses. Yeah, I’m making a point – the characters were well-drawn, distinctive and reasonably memorable but just a tad on the Hollywood side. Remember, I’m nit-picking here for fellow writers, not damning this book with faint praise – it’s a good, ripping yarn and readers will enjoy it on that basis. The stuff about the characters just reminded me to remind myself that every character should have a purpose. A whole bunch of research went into this novel, and it shows. Weir deserves some kind of research medal for the length, breadth and depth of his investigations to make every last detail not only plausible but sufficiently accurate to his readership in the OCD Engineers With Asperger’s community. There’s so much explanatory detail, sometimes I drifted off a little. Weir didn’t lose me, however, and generally threw in something new every couple of pages to keep me engaged. It’s a reminder to fellow writers to do the research, then ditch it and allow the characters to feel their way through story so we also feel the skinned knuckle rather than absorb the appropriateness of the particular sized bolt being tightened. Again, not damning with faint praise – the level of detail Watney gives in his diary is consistent with his fix-it-or-fuck-it engineer character. Just sayin’. Finally, the character of the landscape. I love Martian landscapes sent back by the rovers, so I’m familiar with the colours and textures; with the desolation of low hills and stumbling rocky plains that, unlike Terran deserts, don’t beckon with the promise of an oasis just beyond the horizon. I get the feeling that my stored visuals and imaginings filled in some of the blanks of the Martian landscape because Watney wasn’t that forthcoming about it. For that reason, for me, Mars was more of a painted backdrop in this. It’s not a biggie, but I needed to taste the dirt, smell the sub-zero wind, and hear the aching silence or a muted thud through the almost non-existent atmosphere when spotting a rock-fall. All in all, congratulations to Andy Weir on The Martian - a great premise played out well. If you enjoy a ripping yarn, enjoy. There's more than one piece by Twain to try answering that question, but this is as good a place as any. How Pudd'nhead Wilson was birthed is arguably, to writers at least, as interesting as the story itself. It was originally written as farce, but the unexpected calls of the emerging plot for logic and continuity pulled Twain this way and that, regardless of what he thought about it all. Along the way, certain characters turned out to be not as important as Twain had surmised, and other characters became a good deal more important. In the end, Pudd’nhead emerged as the unlikely hero of what, to Twain’s surprise, turned out to be a tragedy. The fact that it is a tragedy was highlighted by some of Twain’s publishers, whom, perhaps for marketing reasons, called it The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson, something Twain wouldn’t have done because the tragedy doesn’t belong to Pudd’nhead. Other publishers just called it Pudd’nhead Wilson, perhaps to save on typeface, or tried out Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins, presumably to up the intrigue and extract dollars from pockets. Either way, it’s still in publication, like most of Samuel Clemens’ work, and for good reason – he’s an insightful and honest writer. Clemens is sometimes accused of holding to the racism of his time regarding slavery and of ‘negroes’ being from a ‘lower order’ of humanity. I understand why people might think this. Huck Finn does feature a ‘challenging’ portrayal of ‘niggers’, one in particular, as simple. On the other hand, Pudd’nhead Wilson creates the most detailed portrayal of Roxana, a free African-American of the servant class, and her illegitimate son, whom she raises up only to… Well, I won’t include spoilers but all does not go well. The point is that characters are served as characters, and not as ciphers for a racist mindset or ideology. Clemens relishes great care on Roxana’s dialogue. Some might call this racist charicature, but I rather think Clemens was just a good observer, faithful listener and transcriber of the patois. Also, without giving away the tale, one character, raised a certain way, is unable to change his speech or behaviour despite his race being revealed to be other than what he thought it was – in other words, Clemens makes nurture, rather than nature, the main arbiter of human character. That said, Clemens could’ve gotten away with any amount of outright racism back then, whereas portrayal of ‘colour’ is a fraught area for contemporary writers. As an Anglo-Australian, I could write a portrayal of an Irishman without censure, but I would, arguably, come under critical scrutiny writing a person of colour. I can live with that - it’s probably a good thing, as my white culture continues to crawl out of the post-colonial era, racist as ever.

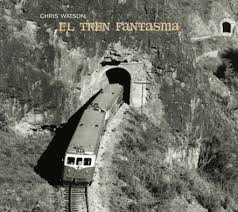

As for the story of Pudd'nhead, it suited being made into a play, and was. The play probably had some success - it has an unlikely and engaging hero, a dastardly villain, a vile murder and a few plot twists. It also discreetly challenges the racist stereotypes of ‘negroes’ as inferior, and highlights the cruelty and injustice of slavery via the threat of ‘being sold down the river’. This sword hangs over every ‘happy’ slave should they lose favour with their ‘owners’. And centre-stage, much more than Wilson himself, Roxana’s agony to do right, her mistakes, her brave fight to thwart injustice and make amends is played out. Roxana’s a complex character – clever but foolish, just but conniving, loving but aggressive, fearful but brave. The villain is a wastrel good-for-nothing, and the plain (white) folk of the town are alternately generous and judgemental. The chapter-headings include bon mots, ostensibly from one of Pudd’nhead’s hobbies – words of wisdom to be included on calendars. These are, I suspect, the only remnants of the farce this tale was intended to be, and are clearly Clemens inserting his acid wit to signal the story ahead. So, Pudd’nhead Wilson is still a good read, has compassionate and philosophical depths, and an honesty that might help ease any accusations of racism put to a Southern gentleman-writer living in a slave culture. Whatever you think of Mark Twain, he was no fool, and, for this reason alone, I don’t think he was capable of believing slavery could ever be, in any way, right. Not a written story, El Tren Fantasma is, however, a narrative that stirred this black heart. Chris Watson, musician (Cabaret Voltaire) and professional sound recordist with the BBC, spent a month on the last trains to make the coast-to-coast trans-Mexican crossing before the service was discontinued. When he edited his recordings, he created something unique and very beautiful. While trainspotters' souls will be thrilled by the authenticity of the sounds, not just of the trains, and their passings, but the towns, stations and quiet spaces across Mexico, others can be swept along on a sound narrative that subtly becomes, not music, but something very close to it. The two most musical tracks have been extended and put on vinyl, which I recommend highly. And no, it's not the dance mix. By the time the final track, and final announcement of the end of the service comes, it arrives with a surge of emotion. It's poignant. It's the end of a story, of many stories. Evocative, impressionistic, finding the rhythms and music within not just the backbone of this narrative - el tren fantasma itself - but also in the spaces and places around the train. This was a time and a place in Mexico; many times and places, in fact. And now it is no more. But Chris Watson has given us this story, a story in sound. (File next to KLF's classic, good-luck-finding-a-copy, horribly-named Chill Out.)

Beautiful and brilliant and much, much more than a bunch of train sounds. On Amazon and Touch Records. I fucking hate cancer. This is another reason why. A wonderful young writer, whom I have a great deal of admiration for, has died.

I'm just going to cut and paste the message from her husband that BoingBoing put up: "Eugie Foster, author, editor, wife, died on September 27th of respiratory failure at Emory University in Atlanta. In her forty-two years, Eugie lived three lifetimes. She won the Nebula award, the highest award for science fiction literature, and had over one hundred of her stories published. She was an editor for the Georgia General Assembly. She was the director of the Daily Dragon at Dragon Con, and was a regular speaker at genre conventions. She was a model, dancer, and psychologist. She also made my life worth living. Memorial service will be announced soon. We do not need flowers. In lieu of flowers, please buy her books and read them. Buy them for others to read until everyone on the planet knows how amazing she was. –Matthew M. Foster (husband)" How could you not love the writing of a woman who hugs a skunk like it was the greatest thing ever? All animals, and animal spirits, should mourn her passing. I warmly encourage anyone who strays by accident to this page to read her work. Now go to Amazon and press some buttons. Unrelenting misery is not a common reason to lend a book to someone. However, a friend did, in fact, lend me Leo Tolstoy’s Master and Man, and Other Stories. I’ve yet to grill him about why he did this to me – I mean, why not just punch me in the face? Too fast? Not enough prolonged misery? No, let’s make it 271 pages, plus introduction, of unrelenting misery. Spoiler alert – everyone dies. Miserably. And deserves to, because they’re all horrible or pathetic or both - other than the horse, which was yet another cruel twist in the torture I endured while reading the title story, Master and Man. I thought the first story in this anthology, Father Sergius, was almost unbearably and unremittingly bleak as it outlined the train-crash of a man’s life, interspersing it with a few highlights of the worst miseries, then ended it with his death. But this, it turns out, was just the warm-up for Master and Man, in which the stony, near-psychopathic avarice of the ‘master’ is reflected in the ‘noble’ but utterly craven ‘man’, who accepts every part of his irredeemably miserable life – the cuckoldry, the alcoholism, the utter poverty, the lack of warm clothes, the corruption of and cheating by his master - with the same fatalism he faces his slow, cold death. The thought of having to read the final, much longer, story in this anthology inadvertently shone a warmer and more positive light on the possibility of sudden and early death. The blurb on the back should’ve been a clue: “These three stories were begun in the 1890’s during the period when Tolstoy, tormented by questions of religion and morality, undertook literature almost as a guilty pleasure.” While I can’t imagine anyone, Tolstoy included, attaching the word ‘pleasure’ to this painful and painstaking parsing of personal pain, I can certainly see plenty of guilt. Tolstoy clearly felt badly about the human condition, and that might account for why every character is riddled with weakness, sin and unresolvable internal conflict that exhibits as bad behaviour – or, if a kindly act is committed, it is so underlain with fear and guilt, and basely motivated, that the guilt of the good is equal or greater to that of the bad. Tolstoy was a brilliant mind and a brilliant, stunningly insightful writer, so while I wished I could suffer a major debilitating stroke that left me blind and unable to complete the book, I was also, like, ‘yo. Dude writes good’, in that simple, honest and unaffected way of all old white geezers who think that having some old Public Enemy cds in their collection gives them license to do so. Tolstoy will rarely be read by those raised in the current purity of contemporary YA literature which commandeth thou shalt always show, never shalt thou tell or thou can kiss any kind of publishing deal goodbye. Editors and most YA authors would flinch at Tolstoy’s unrelenting telling, ignoring the fact that he does show and tell incredibly well. A digression... Even before I became a soap opera writer, I recognised the only other Tolstoy I’d read, Anna Karenina, was a form of soap. This is in part characterised by the depth to which Tolstoy applies his focus to the minutiae of his characters’ internal lives and histories. You are not left in any doubt as to the length, breadth and width of his characters’ misery, and their many failings. It is perhaps true to say there is no such thing as altruism; that every human action and its motives, parsed down to the nth degree, will reveal our reptilian cores, blinking in the light and licking its lips like an Australian prime minister. Tolstoy reveals this reptile with the level of observation practiced by field biologists upon discovering a new species. He allows his characters the full gamut of intellectual and physical torments with the precision of a Mengele, giving the gentle reader an understanding of – and crucially therefore a connection with – each character, so you too can feel a little of that private hell. And eventual, inevitable, inexorable death. The final story, a novella, is a colonial war story - a boys' own adventure. A distinct contrast to the first two pieces, Tolstoy apparently felt guilty about writing such a 'frivolous' piece. 'Frivolous'? Yeah, right. This story's brilliance lies in its portrayal, in just a few brush strokes, of action, motive and context. Its stunning finesse and command of story, and a scattering of exquisite vignettes, sweeps the reader into its 19th century embrace, and the never-ending conflict in Chechnya. And then everyone dies, brutally, and horribly, in the blood and the mud. I think every writer needs to read Tolstoy, every now and then at least, as an antidote to the anoydyne, to the requirements of commercial writing (ie, anything any of us make money from), to the self-censoring and the politically correct, and the impositions of genre and contemporary literary fiction. We need Tolstoy to be reminded life is short and brutal, that hopes are always dashed, things can and will always get worse, and that misery isn't an unwanted visitor but a constant and faithful companion.

Did I enjoy this book? No. Do I highly recommend it? Yes. Ishiguro is a best-selling lit-fic novelist who has risen to the lofty career heights of hardbacks and beautiful cover design. The Buried Giant is a lovely object, with all sorts of bookish touches designed to feel good in ones hands and look good lying about the place. I commend the designers. The content is a curious, dreamy little allegory set in medieval Britain. With history’s ghosts lurking in the unseen distance, the supernatural creeps into the tale, which also references the Arthurian mythos. Sir Gawain, now transformed into a more dour but equally confused version of the White Knight from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, appears and guides our protagonists - an elderly couple seeking to reunite with their son - for some of the journey. Ishiguro uses a great deal of passive expository prose, mixed with first and third person narration, and even intrudes his own authorial voice briefly toward the end. There are jumps forward and backward in time, jumps in focus on character and journey, and a hazy sense of place that befogs the reader as much as the befuddled protagonists, who are caught in mental haze of tattered memory and forgetfulness. So, yes, literary fiction - breaking all the rules genre fiction lives and dies by to paint a more impressionistic picture of people and a world. I have a low tolerance of the wank-factor in lit-fic – especially from debut novelists who think characterisation is for romance novels and plot is for young adult reading. But, having just read Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, I know the bugger can write. Where Remains was a mannered, dry-as-dust comedy of failed romance, skilfully rendered in Edwardian style, The Buried Giant is a very different style of narrative – elegiac and dream-like, meandering from set-piece to set-piece, a little like Alice in fact.

And, also like Alice – though I don’t mean to draw too long a bow on any similarities because there are few - there are a number of levels on which to consider the story. There is a sadness of approaching doom, and the feelings of loss from a past glimpsed only as the mental fog shifts, and hides more than it uncovers. The author, of an age to be farewelling friends and family to death, seeks to bewitch the reader, just as frail bodies and the harsh wounds of time have left the protagonists almost helpless in the mist, their only compass pointing to a son, somewhere, whom they can find if they simply persevere. Like our own journeys, theirs is interrupted and derailed by life and circumstance, and ends the way all lives must end, facing the void, alone. Does Ishiguro pull off this stylistic set of tricks to create a rich and engrossing whole? I don’t like sad books as a rule, but Ishiguro has to be admired here for creating a rich world of fantasy and gloom, mired in medieval mud and a life-expectancy half that of ours. Memories of war and betrayal seep through the text a good deal less than joys of the past but, for some of us, that is the nature of memory – happiness eclipsed by regret, regret hidden and lost by deliberate refusal to remember. The subjects that Ishiguro dwells on in The Buried Giant put character, and to a lesser extent plot, in a support role. Perhaps that’s just how it is with the genre of lit-fic. For me, the book is made worthy by the love and humanity at its heart. I like a novel whose driving force, and prompt for every action of the protagonists, is love. |

Reviews & stuff

Archives

July 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed