|

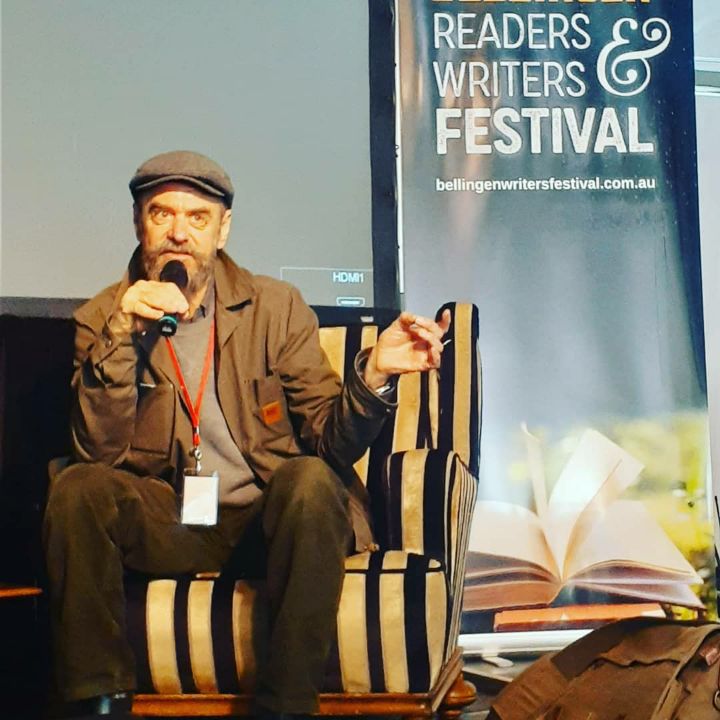

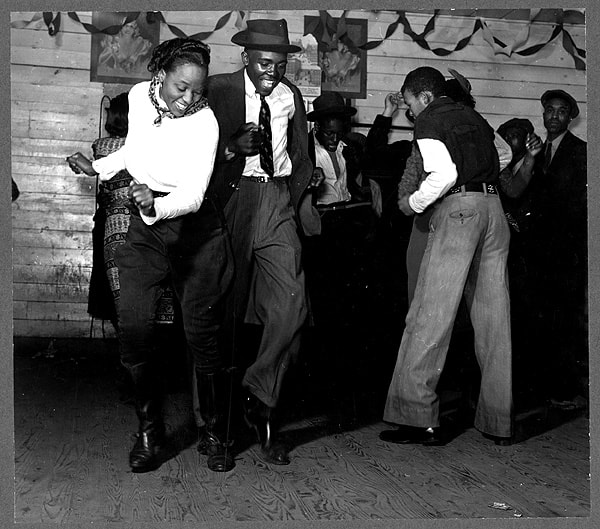

As a ‘festival virgin’, a clueless debut novelist invited to their first ever writers’ festival, I was nervous about attending the Bellingen Writers and Readers Festival. In fact, when first invited, I wondered if I could get out of it. Though dimly sensing only a complete idiot would try and dodge this amazing opportunity, I wondered if I could think up some kind of excuse, or break my own leg – anything that would graciously excuse me from being onstage with other, far better and cleverer writers, facing an audience expecting something more than, “Um, so yeah, the book? I guess it’s like this big, um, road trip and, yeah, stuff happens.” A public speaker I am not. But, I figured I owed my brave little publisher, Brio Books, some payback for publishing me. After all, with no marketing budget and mid-pandemic, literally no one knew about my novel, let alone was buying it. Brio weren’t doing well from their investment in me. So I vowed to go and do my dib-dib-dib best. (I was a cub in the Scout movement for a few weeks when I was about seven, and the only thing that stayed with me was “dib-dib-dib, dob-dob-dob”. No, I don’t know what it means but there’s clearly still a part of me forever wearing shorts and long socks.) Arriving at Coffs Harbour, alone and timid, I was greeted by Liz who instantly relaxed me and took me to my billet, something I dreaded mainly because all I could think about was the discomfort of having to poo in some kind strangers’ house while they were also in it. I know, but that’s how my mind works. And then this amazing thing happened. The strangers in whose house I was inevitably fated to poo in, Beth and Tim, weren’t just nice, super-focused and intelligent in a relaxed and inclusive way, they weren’t just the sort of people who’d ignore me pooing in their toilet – they were immediate friends whom I felt relaxed and happy to be with. I had the weird sensation that they were simply a couple of my oldest friends I’d inexplicably forgotten I had. Now, if one of them needed a kidney, I have one to spare. In other words, I was ready to poo and it would be a happy poo. A whisky hangover later, the next day saw the Festival Opening with the two raconteurs, Miklo (Michael Jarrett), and William McInnes. Miklo brought us together by teaching us all to adjust our POV and ask for welcome to country. McInnes, playing a calculated casualness, appeared to ramble while actually applying the raconteur’s razor sharp wit. Then, a poetry slam, packed with locals trying out their best lines. Young and old, literary and loose, funny and grim, naïve and sophisticated – anyone could and did have a go. It was egalitarian, engaging and funny. It began to dawn on me that I was in a community who loved words and story. Was this my ‘tribe’? Writers advice 101: Find your tribe. What does that mean? For a recluse who lives in a remote mountain valley in Tasmania, it meant little. The idea is that you, as a writer, write in a certain genre, so you need to find those fellow authors, and your readers, who are, ultimately, part of the same ecosystem. For those of us writing multiple genres, unsure where we fit in, or struggling with introversion, finding a tribe sounds like the opposite of what we’d naturally do, which would be to find the quiet corner of the party by the bookcase, and try to blend in with the curtains. So I’m nervous about my Big Day. I’m due on ‘Mornings’ – a chat with Organiser and MC Adam Norris at 9.45, then a speculative fiction panel with Nike Sulway and Rohan Wilson at 1.45 – followed by a book-signing, and finally an author-reading beside the wise and funny international bestseller Michael Robotham, fearless and tender journo-author Mohammed Massoud Morsi, and acutely incisive word-dancer poet Rebecca Jessen at 5.45, followed by another book-signing. Me, the awkward introvert on stage saying…stuff. What can I say about the day I feared most? The day on which my pretense to authenticity as a writer would be cruelly exposed in front of writers and readers smart enough to know bullshit when they saw and heard it. I’m such an idiot. From the moment Adam Norris’ dulcet, radio-perfect voice asked the first questions, I felt myself cupped and comforted by him and our small audience. I didn’t have to try and fail, I only had to be honest and helpful. I didn’t have to please people, I only had to share a little love and insight with them. The spec-fic panel with Nike Sulway and Rohan Wilson had me relaxed and cheerfully sharing what I could, impressed by Nike’s generous moderation and Rohan’s deep and incisive insights into writing and politics. Then, finally, the bit I'd feared most - the author-reading. I asked my fellow authors for advice, and they kindly gave it. “Avoid reading passages with lots of dialogue.” “Don’t read your first few pages.” “Don’t, for the love of God, do accents.” What did I do? I think you can see where this is going. I started by clearing my throat, then, in a heavy south London accent… “Chapter One. My name is Blanco…” My forever thanks to Adam, Liz, Sue and all who organised Bellingen Readers and Writers’ Festival, to my publishers David Henley and Alice Grundy, to my hosts Tim Cadman and Beth Gibbings, to the kind, clever and endlessly wise authors I met, especially Kate Forsyth – a gracious and wise Empress of empathy, Rohan Wilson – a constant font of insights, kindness and boyish enthusiasm, Rebecca Jessen – the soft-spoken word-dancer whose poetry instantly took me to other places and times, Mohammed Massoud Morsi – good humoured rogue journalist and novelist who brought us all, and himself, to tears, Mirandi Riwoe for kind words and great advice despite a teeth-grinding migraine, Michael Robotham – international superstar – who kindly admitted I hadn’t completely fucked up the ‘sarf Larndin’ accent, the audience – a diverse group of people who loved and listened to it all, and finally, those lovely kind people who asked me to sign their copies of The Last Circus on Earth.

1 Comment

In an unexpected plot twist, Blanco and the circus meet up with a 'journalist' in the middle of nowhere - probably somewhere in the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan, as they all travel south following the denouement of Last Circus. Assaph Mehr's excellent interview blog, dedicated to the protagonists of many, many novels, has published the story of this encounter. And for readers of The Last Circus on Earth wanting to see the real star of the book, Daisy, here she is.

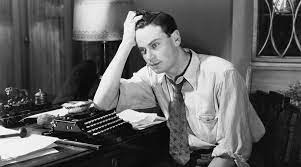

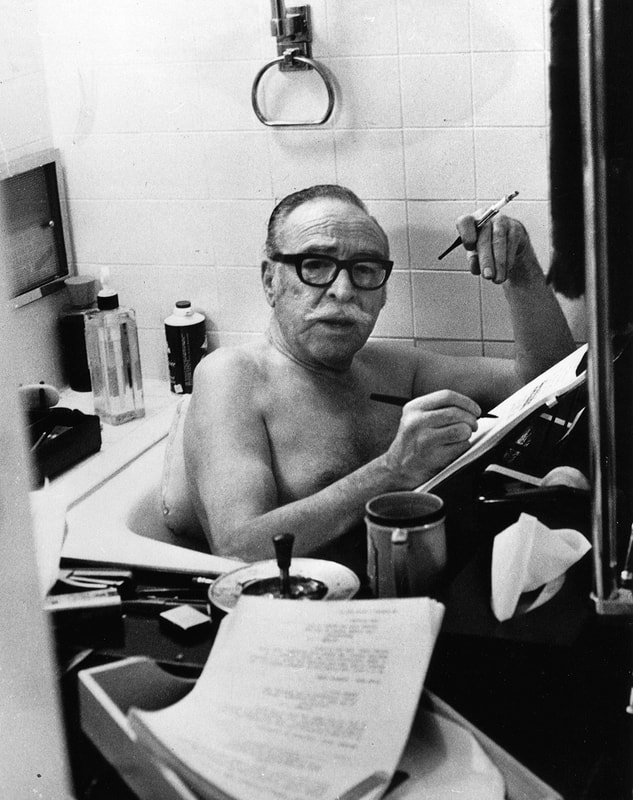

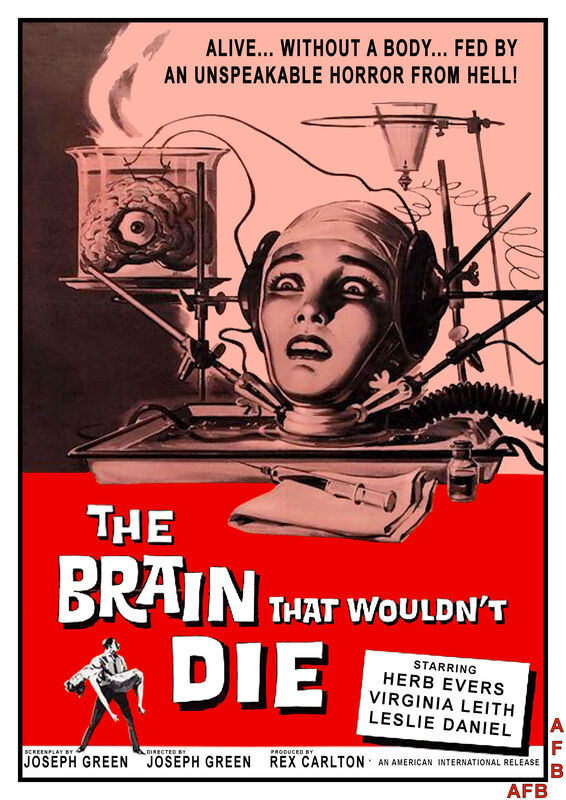

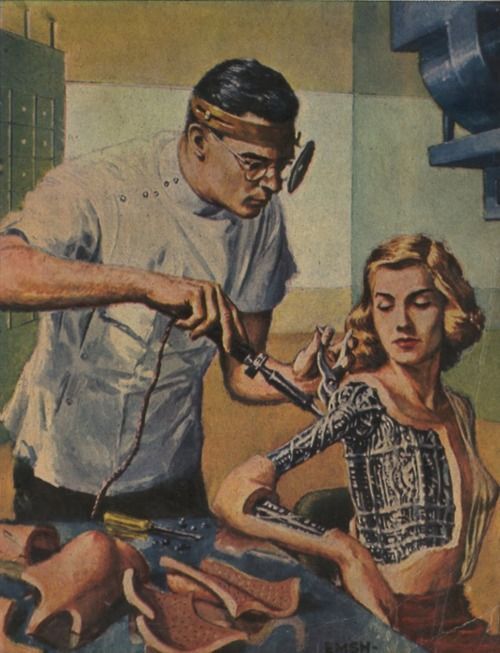

Never been to a writers' festival? Wondering what a writer even looks like? Come to BWF and see us in action! You may be surprised to find that in this modern era, writers now use "computers", and often just input a few general instructions before the "computer program" writes the entire book. That said, there's still a lot of preliminary thought put into those keystrokes! Once the idea takes hold of the writer's imagination, the average novel can take several weeks to write. For some this is a pleasant time... For others it can be a time of considerable struggle. Writers can even suffer from a condition called 'writer's block', which requires immense patience and sympathy for those around them because writers are often selfish bastards who could be doing something useful with their lives, and pretending this isn't the case takes its toll on loved-ones.  It's generally thought that children's writers have the easiest time of it... ...while writers of larger books are necessarily required not only to write a great many more words, but avoid repeating them too often. This can be a challenge. Writers frequently use alcohol or amphetamines, medically prescribed, to assist. Others like to relax to allow the percolation of thoughts to arise naturally, like bubbles in a bath, to the surface of the mind, where they can be transferred to the written page. (*NB, this is known as a 'simile' which is a writer's term for taking the scenic route to the point they're trying to make.) But, however the magic is done, writers are amazing, and the Bellingen Writers' Festival celebrates that magic in sessions which will pit writer against writer, in a winner-takes-all tournament, with you in the ring-side seat as they try and out-clever each other! Come along, heckle, pelt us with produce! Bring the kids and family pets! Nothing like children crying or barking dogs to ramp up the tension while we try to think! See you there!

https://www.bellingenwritersfestival.com.au/people/ The Exploring Tomorrow podcast, by filmmaker, director and writer, Mikel J Wisler, has interviewed me on his wonderful, uber-nerdy show. It was a lovely chat, and Mikel was a warm and charming host. Super-nerdy writers of sci-fi and spec-fic may enjoy the conversation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yLJS6hgeFb0 Last year, in the middle of releasing a debut novel, mid-pandemic, with no marketing plan or budget, I blagged a surprise collaboration with Tasmanian playwright, Stephanie Briarwood, funded by TasWriters. The funding was part of a 'we'd better keep them alive and off the streets' strategy by government to avoid performers and other creatives from being seen in public, so, long-story-short, I co-wrote a kinda, sorta play - a speculative fiction narrative set in the near-future, in glorious down-town Burnie. Intended as a one-hour screenplay, Steph and I didn't know where the work would end up, so we were chuffed to be told Blue Cow were going to do a readthrough-performance - irl! Watching their performance, and skills in action, was wonderful. Stephanie, a seasoned professional, cheerfully mocked me as a 'theatre virgin' when I misted up, made unexpectedly emotional by the characters evolving through their narratives. So, a huge thank you to all involved. I'd love to see the actors encore in an actual filmed version of that one day in the life of an illegal taxi driver, Hong Kong refugee, Wendy Chen, and her growing family of passengers. Anyone need a super low-budget, locally made 100% Tasmanian drama script?

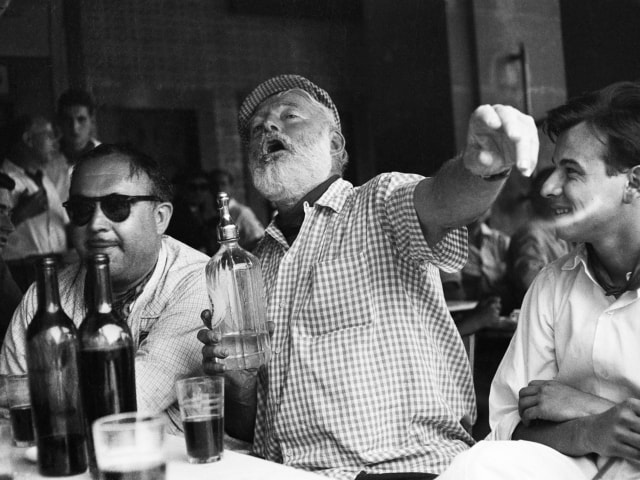

Obviously a mistake has been made. I've been invited to a writers' festival to be some kind of literary cage-fighter with an impressive group of real writers. Having never been to one of these things, I'm honestly not sure what to expect other than heavy drinking and arguments. I imagine it will start out reasonably civilised... ...and then descend into some kind of fierce competitive intellectualism in which the caged writers entertain the bellowing, half-naked crowds with things I'm unfamiliar with, like wit, and bon mots, and incisive insights into la condition humane. Etc. As each writer tries to top the others, and put them down in ever-cleverer ways, things are bound to turn nasty. My strategy will definitely be to get drunk quickly and throw the first punches. My rationale is that, sufficiently intoxicated, blows I fail to deflect will hurt less, and I'm sure to win audience plaudits and tossed coins by being ready to kick it all off. In any event, I've looked at the competition, and I'm pretty sure I can take down John Marsden, Clare Hooper and Bob Brown if I progress to the finals, but first I have sessions with Alex Landragin, Alison Croggon and Nike Sulway, then a 'conversation', presumably in some kind of bear-baiting pit, with Ramona Koval, then finishing the Saturday with an all-in mass-brawl with Koval (if she's still able to fight), Tony Birch, Mirandi Riwowe, and Rebecca Jessen. I hope to see some of you at the bar afterwards! Slainte!

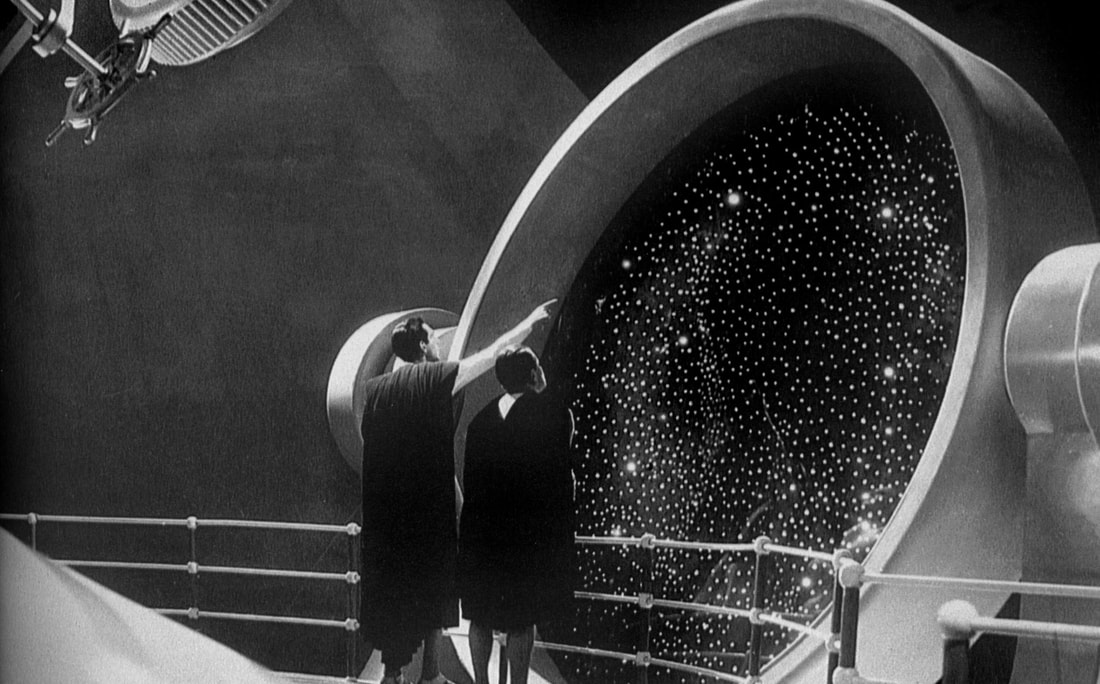

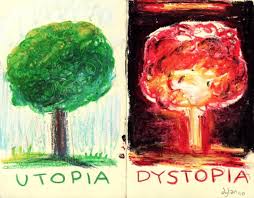

Wondering why humans aren't getting their shit together? Our biology is holding us back. In small tribal groups, most destructive thinking and behaviours are controlled, contained and corrected to that which will sustain the tribe. That’s how we’re hardwired. But on our globalised Earth, forms of meta-intelligence have emerged that overwhelm our individual and tribal intelligences. Organised religions, political ideologies and global corporations, each made up of myriads of functional humans, are working toward the unintended consequences of war, unstoppable climate crisis and mass species extinction. How are the ‘advanced’ future humans and aliens in your science fiction able to function cooperatively and sustainably long enough to evolve beyond behaviours that once served them well but became self-destructive? Individual and collective intelligence aside, how do you design a conscious creature who can achieve what we’re failing at—long-term survival. Here we have another problem. We don’t know what consciousness is or how it emerges—it’s still one of the great frontiers of science. When you drill down, even the term ‘consciousness’ becomes useless. Other than in the strict medical sense (the Glasgow Coma Scale), ‘consciousness’ isn’t even a thing. I, for example, don’t exist. Who is writing this if it isn’t a conscious incredibly nerdy being? If you now punch me on the arm, you may reasonably ask who is feeling the pain if it isn’t a conscious being—an ‘I’. But where are the words forming your question coming from? Is there a mini-you, sitting in your brain at a big meaty control station, working at lightning speed to collate thoughts, edit words and issue your response? Nope, it’s all just collectively emerging from specialised meat, linked by basic chemistry and physics. As we talk, we have no awareness of what’s happening in our brains to enable us to do so. Physiology and scans don’t tell us how our sense of self can appear certain when all indicators are that it’s merely a recursive representation—an avatar to assist the global brain function at ‘higher’, differently effective, and affective, levels. A dog is perfectly intelligent in its own way. So is slime mould, so is a young child—and they all need to distinguish ‘self’ from ‘other’. But they are conscious in a different, less complex way to us. The thing we call ‘consciousness’ is an evolving, ever-changing spectrum, in multiple dimensions. Worse, there’s a second way ‘you’ don’t exist. The ‘you’ reading this now, isn’t the same ‘you’ playing sports, or fuming in a traffic gridlock, or drinking in a bar, or making love. In effect, you’re multiple-personalities in a single body. In all your different emotional states—from incoherent-with-anger to kindly-altruistic—‘you’ are a bunch of very different people. Most of us are writing dystopian speculative fiction for good reasons, and lack of IQ in our leaders isn’t the issue. So, if you’ve designed your ‘superior’ homo or alien with a bigger brain, their ‘smarter’ intelligence isn’t a guarantee your new species will survive any longer than ours. We’re social mammals evolved to engage constructively with others and we do it spectacularly well. True, we’re only evolved to cope with a maximum of around 150 others in a tribal group rather than the entire interweb, but we can still operate collectively to build civilisations, tech, philosophies, the Rule of Law, and political parties—all of which require incredible individual and communal skillsets.

We’re also already hugely empathic as individuals and compassionate as collectives. Our intensely emotional brains motivate us to reason and problem-solve on every scale from the individual to the global. Yet those capabilities are not enough to stop us from committing civilisational suicide. It’s no longer enough to casually claim our fictional advanced creations are ‘wiser’ or ‘more empathic’ or ‘more compassionate’ or ‘more augmented’. We are already those things. So, when you create a new homo species, or our new alien overlords, what is the critical difference that has allowed them to transcend their biological evolution? How have they avoided collective suicide? What, in other words, could we do to save the most complex object in the known universe from destroying itself? Good luck. Okay, so there you are, wearing a lab coat, in a lab, brainy af, with billions of research dollars available to back up your idea to create an artificial intelligence (AI), which you hope will basically be better, smarter and wiser than us, and will save us from ourselves. Is it feasible? For all the hype about AI, and fears of exponentially self-evolving AI turning into a ‘Singularity’ that will rule us all, AI is just algorithms and algorithms do not a singularity make. They can build cars. They can hound and harass welfare recipients. Can they feel wistful during a poignant moment in a Vivaldi concerto? No. Just because you might be able to design an AI that passes a Turing Test, that doesn’t mean it can perform the most critical level of intelligence underpinning it all—emote. And in case you think emotions are a useless by-product of human reasoning, you’ve got it backwards. First, we care. Then we think about why we care. Then we act. Make your AI algorithms as recursive as you like, but you’ll never make it care. Okay, so how about renovating homo sapiens? Transhumanists are a diverse group, but they, like most sci-fi writers, tend to focus on physical and mental ‘augmentation’. But we are already massively augmented. Mentally, the phone in your hand augments your brain into the global consciousness. You’re also physically augmented. Need to connect two pieces of wood? Transform your entire body via a hammer and a nail. Need to travel distant places fast? Buy a plane ticket. Need to leap tall buildings? Take the elevator. Also, critically, transhumanism is inherently fascist and, with the best will in the world, missing the point. The idea of an ‘ideal’ human ignores the historical and biological reality that, in a group, diversity is strength—even if it looks like and sometimes is a weakness. The Third Reich wasn’t a failed plan but a Big Lie. So, when we writers think we’ve created a ‘superior’ or ‘advanced’ human species—or a truly novel alien species for that matter—we’ve merely transposed fascist, racist and colonial templates onto the future. Just as the English thought themselves superior to First Nations Australians, so our fictional future humans or aliens are largely versions of the Colonial Lie—which is that tech, or appearance (pale skin), or bigger guns, or culture, make us somehow ‘better’. But how are post-colonial humans ‘better’ if we’re not sustainable on a global scale? What’s stopping us being better? Biology.

Sci-fi and spec-fic routinely tell stories which involve 'advanced' humans or aliens - usually cartoonish extrapolations of ourselves. Over the last few decades a common trope is the 'AI' which becomes too human, or decides that humans are, for one reason or another, dangerously redundant. Artificial intelligence, if allowed unlimited development, might begin to guide its own evolution into a mind far beyond our means to comprehend - or control. The pinnacle of this speculation is commonly referred to as a technological singularity. Sadly, for the most part, writers use an intelligent 'singularity' as a poorly thought-out McGuffin, a deus ex machina plot device to serve the needs of the narrative. When I found my speculation about the near future heading in this direction, I was primed to reject even the concept of a singularity, largely on logical grounds. It can also be a cop-out for a writer to imagine a creature with vague 'super-powers' without thinking through what that might mean in a plausible alternate reality. My traveling circus in The Last Circus on Earth isn't what it seems, nor it's malignant leader, Mister Splinter. But as we head toward various forms of global collapse via global warming and the extinction crisis, I wanted to challenge the thinking and solve the problem at the heart of it all. How can we humans, and our myriads of cultures, survive the ruin we are causing to our planet and ourselves? So, for what it's worth, here are a few of the questions and problems I posed for my extremely unpleasant circus owner, Mister Splinter. If humans cannot overcome those forces destroying us, given unlimited funds, how could we build a better, 'advanced' human to survive beyond us? One who wouldn't create another smoking ruin of a planet, and would instead learn, adapt, nurture and prosper into the distant future. What things would we change in this new human to 'make them better'? Should we make us stronger? Fitter? Prettier? With heightened senses, and metabolically more efficient bodies? Would we give them a higher IQ? Greater focus? A new, more sophisticated global language? Is 'smarter' wiser? Do any or all of these tweaks advantage the individual in a meaningful sense? Do they advantage the wider community? Would emotion and reason, the two sides of the same cognitive coin, be unbalanced in a new ratio? Would ideology and religion be redundant? Would we still be social animals who demand and need communion? Would we be happier? How would governments and economies differ in a better way? What would stop narcissists, sociopaths and liars from taking over? And what if, in the middle of all this study and experimentation, tweaking genes, new tech and ideas, your time ran out, your unlimited funds disappeared, and there was a global collapse of societies and nation states? What if those years of multi-disciplinary research was about to die along with human civilisation. Worse! What if your ideas of a new human were fundamentally flawed and naive? What if the idea of a singularity was revealed to be ridiculous? And, finally, what if it was just you, a drug-addled and gene-ravaged researcher, a man now calling himself 'Mister Splinter', who understood all this, and had one idea left to try, and one rapidly diminishing chance to achieve it? How far would you go to save civilisation? How much pain would you inflict on your Frankenstein's monster? On a young man called Blanco... Illustration: Dylan Glynn, sourced from Veronica Sicoe's excellent blog, I Abduct Aliens.

Making the shortlist for the 2020 BookLinks Queensland Mentorship for The Fox was a real boost. Looking at the other authors on the shortlist, I genuinely resigned myself to applauding the deserving winner, so I wasn't too hurt they didn't mention my work during the preamble. It was a jaw-drop when my entry won the mentorship with Robin Sheahan-Bright. Author, editor and publisher of literature for young people, Sheahan-Bright is a multiple award-winner and publishing consultant. Will my gritty tale of a young man, living under the thumb of his father on a remote lighthouse island to the north of Hokkaido at the start of the Pacific War, find favour as an adventurous coming-of-age story with Robin? Or will her highly experienced counsel place me firmly back at the bottom of the literary mountain, bracing myself for a total rewrite? Writing isn't for the faint-hearted, and mountaineering persistence is required for every edit. As of today, Robin is reading my work. I'm strapping on the crampons. [Below is Todojima, a tiny island where this novel is set.]

|

Reviews & stuff

Archives

July 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed